Radio Articles

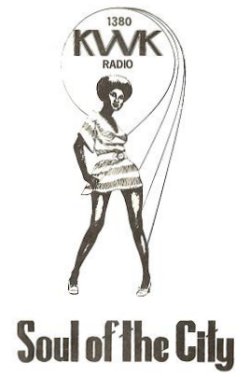

The “Soul of the City” Was Short-Lived

For a short period of time KWK reared back and became the “Soul of the City.” The idea was great, but the deck was stacked against its success.

The station had been forced off the air by the Federal Communications Commission in 1966, following a fraudulent contest. An interim owner, Karin Broadcasting, ran the station for awhile, programming middle-of-the-road music. In 1969, the F.C.C. decided the ownership question, and broadcast veterans Bernie Hayes (Music Director and Operations Manager) and Albert “Scoop Sanders” Gay (program director) were brought in to program the station under the new ownership – Hayes from KATZ where he had been hired a year earlier, and Sanders from KXLW. They assembled a superb staff and the station introduced the new format the first week of August.

It had not been an easy road to that sign on. Eight groups had competed for the permanent license. After a protracted legal battle, a compromise was reached giving Victory Broadcasting 75 percent ownership and Archway Broadcasting 25 percent. Clifton Gates was the lead man for Victory. Joseph Vatterott headed Archway. The new company was known as Vic-Way Broadcasting.

When the new format hit the air, KWK’s listeners were quick to protest. They didn’t care about the behind-the-scenes ownership machinations. All they cared about was the loss of their format and disc jockeys. The employees of Karin Broadcasting also rebelled. They protested to the F.C.C. that Karin was still the station’s rightful owner.

The resultant chaos brought huge financial losses (about $1,000 per day), and the new owners were unprepared to cover them On August 15, listeners heard an announcement that the station was shutting down for a few weeks so facilities could be built for a studio and transmitter. Ten days later, the station was back on the air. Previous employees of Karin Broadcasting had been fired. A couple of those former employees stormed the station’s studios on a mid-September night. The resultant lawsuit seeking a restraining order alleged two Karin people attempted forcibly to remove Vic-Way workers from the studio.

By the end of 1969, things were looking up for Vic-Way. The Ford Foundation announced it was loaning the company $500,000, to be matched by loans from local banks. This, Gates said, would provide the capital to build needed facilities. KWK also announced it was providing free ad time to Negro businesses. Meanwhile, staffers Al Waples, Don St. John, Bill Bailey and Al “Scoop Sanders” Gay set out to win over the market’s teen audience.

The first surveys following the format change found KWK sweeping past its competition, KATZ and KXLW, grabbing a huge segment of the Black audience and many white listeners as well. New names appeared on the station’s roster, including Jim Gates, Tom Joyner, Bill Moore, Jake Jordon, Sonny Joe White, Tony “Slinky Slim” Stitum, Donn Johnson, and Mark Gordon. Black recording artists like James Brown, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder and Billy Eckstein stopped by the station for interviews when they were in the area. But in spite of all the programming success, the combined ownership setup was not working.

The bed of roses came to an end in May of 1972 when the station’s disc jockeys and newsman walked off the job. They said they were protesting several moves by a new management team, including the removal of Bernie Hayes from his operations manager position. After the strike, Hayes and Sanders were hired at KTVI-TV. Then came a lawsuit from the radio station’s landlord over $18,000 back rent. In December of 1973, KWK was declared bankrupt in federal proceedings.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 09/2007)