Radio Articles

The Night The Tower Came Crashing Down

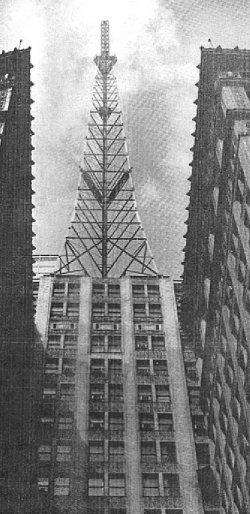

It was the early days of FM radio. March 27, 1955, owner Harry Eidelman signed on his new FM station in St. Louis, KCFM. Studios and tower were in the Boatmen’s Bank Building on Olive downtown. Later, Eidelman moved to a new location to save money.

With the help of broadcast engineer Ed Bench, Eidelman moved the entire operation, including the broadcast tower, to an old warehouse at 532 DeBaliviere. The new 300-foot steel tower was self-supporting and didn’t need guy wires, but the legs literally came down through the building’s roof and were anchored in the floor.

Original KCFM tower atop the Boatmen’s

Bank Building on Olive downtown.

At the time of the move, KCFM was one of six FM stations serving the market. Theirs was a “beautiful music” format, but advertisers were reluctant to put their money into the relatively new medium and the station operated on a shoestring budget. Two of the FM stations here were non-commercial.

Things went smoothly, until the night of May 12, 1960. That’s when Eidelman got a phone call at home around midnight from Walter Vernon, the announcer on duty, who said he saw smoke in the studio coming out of an air conditioner. Writing about the incident later in the Post-Dispatch, Eidelman recalled he “gave him the only advice I could come up with at the moment! Call the fire department and get the heck out of there.”

Vernon, the announcer, did as he was told, and the janitor on duty was quick to follow. The first alarm was struck at 12:12 a.m. At about the same time, someone passing by the building saw smoke and ran to Engine Company 30 at 541 DeBaliviere, across the street from the studios, to alert firemen there. The radio station quickly filled with thick, black smoke and flames burst through the roof, causing another major problem.

The excessive heat had begun to melt the steel tower legs.

Within moments, the huge tower came crashing down. It fell to the north, into the National Food Store at 546 DeBaliviere, setting off that building’s sprinkler system. Multiple fire alarms were called with a total of 25 pieces of fire equipment and 100 firemen dispatched to the scene. It took firemen several hours to get the situation under control, and Harry Eidelman’s radio station was set at over $50,000 – a total loss.

The supermarket suffered smoke and water damage and there was also smoke damage in the nearby Winter Garden Skating Rink, The Toddle House and Hampton Cleaners. Two firemen suffered minor injuries on the scene.

In his Post-Dispatch article, Eidelman wrote, “…there was nothing left of the building that had been KCFM. DeBaliviere looked like the Fourth of July. Within an hour, every member of the staff was standing in the street looking at the ruins.

“The next morning we gathered at the ashes and tried to decide where we could go with KCFM now. We could take the insurance money, which would not pay off one-third of our bills, and fold up. Or, we could try to rebuild something. The consensus of the entire staff was, let’s go forward. They even offered to go without their paychecks until we were back in business, but that didn’t become necessary.”

Ed Bench remembered, “I salvaged a transmitter cabinet and all the parts I thought I could use. We rented a storefront across the street and I cleaned up the stuff I had salvaged and built a one kilowatt transmitter.”

Within five days KCFM was back on the air, operating with reduced power and using space on its old tower atop Boatmen’s Bank, which was, by then, the primary tower for KETC-TV (Channel 9). Within a few more days, KCFM was operating at full power. Ed Bench recalled in a later interview that only one of the market’s radio managers offered help: Robert Hyland of KMOX.

Eidelman reminisced about those trying transitional days several years later. He told a Globe-Democrat reporter he was listening one night a few weeks after the fire when the music suddenly stopped. He rushed downtown, took the elevator to the 19th floor, ran up the last two flights of stairs and rushed into the studio, where he found his announcer fast asleep, the classical record still spinning with the turntable needle at the record’s center.

A year later, KCFM’s DeBaliviere location had been completely rebuilt, along with a 500-foot tower at the site. In 1978, Harry Eidelman sold KCFM to a national corporation, Combined Communications.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 5/08.)