Print Articles

Theodore Dreiser-Globe Reporter

An Alton Disaster Brings Out a Young Reporter’s Talents

One [January 21, 1893] afternoon [Theodore Dreiser] was idling at the Globe-Democrat office when a man burst in and told him excitedly that a passenger train had run through an open switch and crashed into some tanker cars filled with oil on a spur track three miles from Alton, Illinois. None of the editors were in at the time, so Theodore hurried to the scene on his own initiative, planning to telegraph his copy from the station.

Shortly after he arrived there was a tremendous explosion. Flames burning around the tanks had caused two unruptured tanks to heat up, turning them into huge bombs which hurled a fiendish shrapnel – jagged chunks of white-hot metal and scalding goblets of oil – onto the crowd of bystanders: “Many forms were instantly transformed into blazing, screaming, running, rolling bodies, crying loudly for mercy and aid. These tortured souls threw themselves to the ground and rolled about on the earth. They threw their burning hands to tortured, flame-lit faces…They clawed and bit the earth, and then, with an agonizing gasp, sunk, faint and dying, into a deadly stillness.”

Goyaesque scenes of horror passed before his eyes; he tore off his coat and tried to beat out the flames on one shrieking human torch, to no avail.

All the while his mind was recording the carnage, thinking how to describe it. When a train bringing doctors and nurses arrived from Alton, he hurried to the depot where the dead and dying were taken. He watched physicians bend briefly over the charred figures on the litters. Most of them were beyond help. He automatically recorded the name of each doctor and other details. An “accommodation” (local) train was commandeered and the victims were placed aboard. Theodore came along and rode to Alton, where waiting wagons carried the sufferers to St. Joseph’s Hospital. He saw dirty, oil-soaked rags being cut away from bodies, laying bare scorched skin, swollen lips and noses, and “eyes that were either burned out or were flame-eaten and encrusted with blood and dust.”

A throng of relatives wandered about vainly seeking a recognizable face among the seared masks, whispering comforting words in their ears when they found a loved one. A group of parents, whose children had gone to the site of the wreck, milled in the hall asking for information. Theodore decided to act. He went from stretcher to stretcher, asking the occupant his or her name and address, telling those who protested, “Someone will want to know about you.”

“To those inquiring the list was read, and as the last name was spoken, and ‘that’s all’ ejaculated a score of sighs were heard, for many an anxious heart knew that a loved one was not in the list.”

Later in the afternoon a train arrived bearing more victims. Some begged the doctors to kill them. “I’m blind,” moaned one. “Oh, to be without eyes, to have the light shut out forever, that is too much. I want to die! I want to die!” Then, “a loving mother bowed low over the moaning form and buried her tear-stained face and misery-convulsed form in the clothing that shielded her son.”

By then Dick Wood had arrived to sketch the scene, but he was in a state of shock and kept muttering, “It’s hell, I tell you.” Theodore sent him to gather additional details and returned to the explosion site to interview eyewitnesses, who told of narrow escapes or of futility trying to assist agonized victims. A man aiding one human torch cut away the man’s clothes; in pulling off the sleeve of his coat, the skin of the victim’s hand stuck to it and came off like a glove. “I tried …to console him in his awful plight…He recognized my voice, and, with his burned and sightless eyes turned toward me, he managed to inform me that he was my old friend, James Murray.”

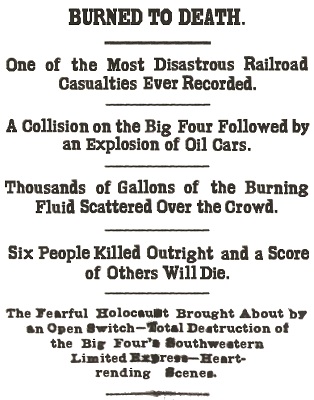

Finally, the city desk ordered Theodore to return and write up his story. When he arrived at the newsroom, reporters who had already read his brief telegraphed dispatches were talking excitedly. He went straight to his desk; as he finished each page, a boy would snatch it away and run to the copy desk. A knot of reporters gathered around him. At last it was done, and the next day’s front-page headlines proclaimed:

The next day Theodore went out again to compile further grisly details and to cover the coroner’s investigation, which was in progress. The two accounts add up to a remarkable job of reporting – long, vivid, gruesome (in the style of the times), yet ballasted with facts. Such was Theodore’s lack of confidence in himself, however, that in the aftermath he was seized by a fear that he had been wrong to chase after the story without getting permission. Mitchell (his boss in the city room), who disliked him, might think he had a swelled head; perhaps he would be fired. He was so late returning from his second trip that he missed his daily assignment, so when Mitchell told him that McCullagh wanted to see him right away, his heart sank.

“You called for me, Mr. McCullagh?” Theodore asked timidly.

“Mmm, yuss, yuss!” the editor replied, not looking at him. “I wanted to say that I liked that story you wrote, very much indeed. A fine piece of work, a fine piece of work!” He reached into his pocket, extracted a thick roll, and peeled off a twenty dollar bill. “I like to recognize a good piece of work when I see it. I have raised your salary five dollars, and I would like to give you this.”

Theodore took the bill, muttered his thanks, and stumbled out the door a reporter.

(From Theodore Dreiser – At the Gates of the City Volume 1 by Robert Lingeman, Putnam, 1986)

(Following is the account published in the Globe-Democrat Sunday, January 22, 1893.The only editing done was the removal of the list of the names of those killed and injured.)

One of the most appalling and disastrous wrecks that has occurred in years followed the negligence of a switchman on the Big Four road at Wann, Ill., yesterday morning. Passenger engine 109, drawing the Southwestern limited express of four coaches, headed east for New York, , crashed into an open switch a half mile north of Wann, a joint station of the Chicago and Alton and the Big Four roads, where seven oil tanks stood in line on the side track. The result was a fire, and later an explosion in which life and property were destroyed. The dead number six and the wounded twenty-two.

The Explosion

The crashing of the engine into the side-tracked oil tanks was not disastrous in itself. The consequent explosion and fire that occurred two hours later caused the terrible havoc, but not among the passengers. It was the sightseers from Alton, Ill., who suffered the loss of life and limb. The Southwestern limited train that leaves St. Louis in the morning for New York and arrives at Wann at 8:48 a.m., was thirteen minutes late. At Wann, which is a flag station, there is no side track, but a half-mile further on, opposite the little cluster of houses known as Alton Junction, several tracks are laid side-by-side with the main line to permit switching and the taking on of cattle from a stock yard which is there. On one of these tracks several oil tanks filled with refined lubricating oil and consigned to the Waters-Pierce oil company of this city, were left standing by the switch engine of the Vandalia Line, which brought them there from Beardstown, Ill. The switchman who has charge of this section is R. Gratten who, it is said, is both a switchman and a barber, managing to eke out a precarious existence by combining the salaries of the two. To this gentleman’s door is laid the entire blame by more than one employee of the Big Four. Last evening, it is said, he left Alton Junction, his home, for parts unknown.

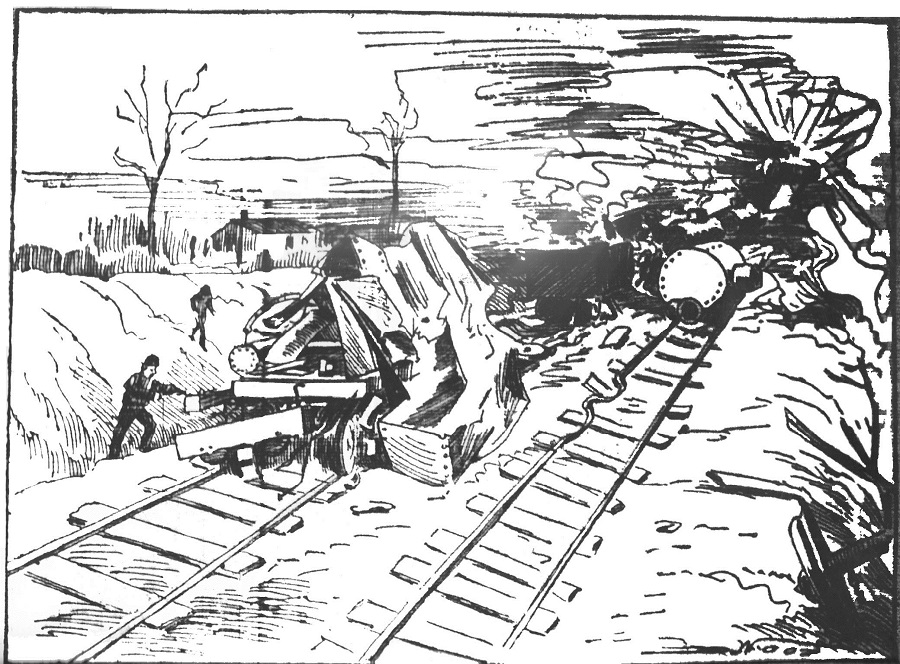

The Fatal Crash

When the limited arrived the switch was still open, Rushing along at a speed of fully forty miles per hour the limited rushed into the switch and on, fairly over the tanks, splitting two of them in twain and throwing the rest crushed right and left. The engineer, Webb Ross, and the fireman, Dick White, both saw the danger. White swung himself from the side of the flying train and ran out across the fields. Webb Ross stood manfully to his post, reversed the lever and threw on the air brakes, but to no avail. The velocity overpowered all opposition. Ross stood the shock and still found time to leap from the cab. Almost instantly, however, the burning oil had spread about the engine and the ground was a seething sea of flames. Into this he plunged – a break for life. The flames burned away his garments and scorched his body into a blackened mass. He emerged from the flames only to fall dead at the top of the bank that led from the track. Next to the engine was the baggage car and café car, the occupants of which were badly shaken up and thrown to the floor. The same condition affected the passengers of the three remaining palace cars, but further than that no one of the thirty passengers was injured. They rushed to the doors on realizing the catastrophe and made good their escape. The flames soon spread from the tank to the cars, and for several hours they burned fiercely in the morning breeze. In the baggage end of the first car were the mails, eleven pieces of baggage, and a corpse, which was being forwarded from the Southwest to Boston. The body was that of Mrs. Morrison.

The Second Explosion

The passengers gathered about the blazing wreck and began looking for anyone who might need assistance. The villagers from the little town of Alton Junction rushed to the scene; word was telegraphed to St. Louis, Alton and neighboring points, and the company ordered a wrecking train with a score of physicians to the scene. The news of the burning wreck brought hundreds of sightseers from Alton, which is only three miles north of the wreck. They gathered about viewing the flames and chatting idly. At 11 o’clock the horrible addition to the already shocking story was made. Two of the remaining tanks, apparently not yet affected, reached the climax of self-containing heat. An explosion followed that shook the ground for miles about. Seething, blazing oil was showered upon the onlookers, thrown high in the air and over onto the comfortable cottages of villagers who lived by the roadside. The scene that followed beggars description. Many forms were instantly transformed into blazing, screaming, running, rolling bodies. crying loudly for mercy and aid. These tortured souls threw themselves to the ground and rolled about on the earth. They threw their burning hands to tortured, flame-lit faces, from which all semblance to humanity had already departed. They clawed and bit the earth, and then, with an agonizing gasp, sunk, faint and dying, into a deathly stillness. The horrible holocaust had been accomplished. Five souls had been burned into eternity and twenty-two had been maimed, blinded, burned into an unsightly condition that made every face blanch and every heart shudder. In all this awful holocaust distraction and frantic fear held away.

Paralyzed With Fear

People perfectly safe and unharmed stood wringing their hands, crying out in useless fear or rushing madly to and fro in almost an agony of despair. The explosion gathered together all those who had previously left the wreck, or had as yet not heard of it. They gathered in throngs, but their presence was ineffective and entirely useless. Water would not quench the hissing, flaming oil, and more than that, water was not to be had. The little village of Alton Junction has no water supply except a few wells. The explosion drove the shattered mass of iron with fearful velocity far across the fields. Some of it fell close at hand, however, and pinioned the bystanders beneath its weight of molten heat. The wires overhead leading to St. Louis were melted, fell to the earth, severing all direct connection with the city.

The only alternative was to bring aid from Alton, Ill., three miles away. At 11:30 a.m., the train arrived bearing the medical staff of St. Joseph’s Hospital, with the exception of Drs. W.R. Haskell and T.P.P Yerkes, who had left in the early morning in response to the first call for aid. The second call brought Drs. W.H. Haliburton, E. Guelick, Figenbaum, Scheussler and Fisher, of Alton; also Drs. Gross and Thomas of Gillespie. They hurried from the wrecking train to the scene and superintended the removal of the bodies. Shutters and cots were brought from various little homes and the moaning victims were wrapped in blankets and cloths and carried to the Big Four station at Alton Junction. The scene at the little frame depot was exciting. A great crowd stood about and blocked the entrance way to the various rooms. One by one the litters came, borne by strong, willing citizens who drove back the morbidly curious and filed into the little depot waiting room.

Caring for the Injured

Here the couches were arranged side by side, and over each one a physician bowed for a few minutes to see just how serious the wounds were. Nothing could be done, for no lint or ointment could be applied that would ease the blackened flesh and bones of the half-charred frames. Every now and then the cover was slightly raised to see if life still remained. The gents’ waiting room would only hold five bodies, and when that number had been laid side by side the north room was cleared of benches and the coming litters arranged in this also. There were still others, and out on the platform they were tenderly cared for by the self-appointed nurses. The others were carried across the fields to the little cottages, where the families ministered all that could possibly ease their suffering. By 12 o’clock the Mattoon accommodation train was ready to depart for Alton. In the four coaches and baggage car the dead and the dying were deposited. The work of loading the dead and dying was another appalling spectacle. Out from the waiting room were borne the litters and gently lifted into the cars. From out of the little cottages the wounded were again borne, followed by all the villagers, talking and gesticulating, but in a mournful, subdued manner. When the train had been filled the signal was given and the hospital train was off. Notice was telegraphed to the Alton Police and Fire Departments, who prepared to assist in removing the bodies from the train to St. Joseph’s Hospital, which stands on a hill overlooking the city. The accommodation stopped some seven blocks south of the regular station to permit a short cut to the hospital. At this point were gathered a score of wagons, prepared to do duty as ambulances. Here, too, had gathered hundreds of the local residents who had heard of the awful wreck. It was with difficulty that the crowd was forced back from the cars and the bodies lowered. Then started the succession of wagon journeys to and from the hospital that in no time lined the way with thousands of people gaping and talking in an anxious, nervous manner. From every window and doorway, in back and front yards, on the stoops and hanging on the fences that lined the way the people looked out and down on the procession.

At the Hospital

From the railroad track to the hospital gate is three straight blocks, ascending very rapidly to the crest of the hill, where St. Joseph’s stands. The ascent was necessarily slow and gave ample time for the crowd to satisfy its curiosity. Before the hospital door another immense throng was gathered, anxious and almost determined to view the unrecognizable faces that passed on litters through the entrance-way. Inside all was confusion and hurry. Dr. Haskell, the physician in charge, returned with the train and hurried to and fro, gathering about him his staff and urging his assistants to great speed. The sick of the hospital are attended by the Sisters of Charity, and they busied themselves in taking the suffering to the respective rooms. In a little while three rooms on the main floor were filled with the wounded. The sick that had occupied them were borne out into the hall or carried into other rooms less crowded. The work was lovingly, anxiously done. Each sign and groan of pain found an echoing response in the heart of the self-sacrificing attendants. One room was cleared for surgical purposes, but was not used until all of the first train had been cared for. The scenes in the rooms where the wounded had been removed from the rough temporary litters into the snowy couches were heart-rending. The removal was necessary, however, and much as the victims shrieked and groaned, the work went on. Lying on the couches, the dirty, oil-soaked rags were cut away from the bodies and laid bare the horrible work of the burning oil. The hands and faces of all were scorched, torn and bleeding. The lips and noses were swollen and distorted, and the eyes were either burned out or were flame-eaten and encrusted with blood and dust. The hands of many were burned to a crust, fingers were missing and arms broken. Several of the victims when uncovered were found to be without cuticle, the flames having cooked it and burned it until it either clung to the clothing on removal or fell away of its own accord.

The Search For Lost Ones

When all arrangements were made the public was admitted. An eager throng of mothers, fathers, wives and daughters hurried along the aisle and into the chambers of suffering. Here they viewed each face, but in many cases without avail, for the forms and faces were unrecognizable. By dint of questioning, many of the sufferers were induced to reveal their names. These were taken down by the Mother Superior, Mary Joseph, who preserved the list to guide the inquirers. Soon by each bed, with anxious, tear-stained faces and disheveled appearance, stood the relatives and friends whispering words of comfort into the dying ears, sobbing words of cheer that were half-choked in the utterance. Many of the patients recognized the voices of friends and friends and moaned appeals for aid, for to be spoken to, cheered, lifted up and the like. In the main hall stood a throng of anxious parents whose boys had gone down to the wreck in the early morning and had not yet returned. They appealed to the physicians, the Little Sisters and the attendants generally for information concerning their missing children. A Globe-Democrat reporter entered the chamber of suffering and went from couch to couch inquiring from the distorted occupant his name, age and address. After and long period of waiting and general questioning, the list was completed and he returned to the hall. To those inquiring the list was read, and as the last name was spoken and “that’s all” ejaculated, a score of sighs were heard, for many an anxious heart knew that the loved one was not on the list.

A Second Hospital Train

A Second Hospital Train

At 3:30 p.m. a second hospital train that had been sent to Wann by the railroad company returned to Alton. At Wann the same scenes were re-enacted, and at Alton the same crowd lined the way to watch the progress of the painfully thrilling work. This train brought four bodies from the scene of the disaster. They were those that had since been prepared for the journey, having missed the first train. The progress up the hill was none the less interesting. The throng at the gate, though having watched without food and drink during the long hours of the morning, were none the less eager in their looks nor none the less backward in pressing forward to look at the bodies. The work of the noon hour had nerved the attendants and practiced their ability in taking care of the unfortunates. So they were received and placed with rapidity and ease. In the temporary department of surgery the unfortunates were borne one by one. In this three surgeons stood ready with knives, cotton and lint bandages and plenty of ointment. The victims were stretched out, their clothes cut away, and their wounds dressed and bandaged. Most of them were horrible burned all over, instead of in splotches, and every breath of air seemed to give them the most intense pain. The majority were fully conscious of their awful condition and asked to be handled carefully. Some were stronger than others and wanted to move about.

Begged to Be Killed

Several begged to be killed, that they might be free from their pain. “Oh, I’m blind,” moaned one; “I feel that my eyes are gone. Oh, I could stand all, everything. I could be burned with satisfaction; I could be crippled or deformed forever, but to be without eyes, to have the light shut out forever, that is too much. I want to die! I want to die!” and then a loving mother bent low over the moaning form and buried her tear-stained face and misery-convulsed form in the clothing that shielded her son. Several little boys were among the victims, their moanings were the source of much distress to all the others. Still others were only slightly injured and deeply congratulated themselves upon their luck in escaping at all. One of these, Charles Hammond, a track-walker for the Big Four, had escaped with the loss of his hair, several severe scalp wounds and a burned hand. He sat in the corridor of the hospital, solemnly viewing the proceedings. In reply to questions from a Globe-Democrat reporter Mr. Hammond said: “I am a track-walker for the Big Four, traveling between Venice and Alton at night time, and my home is al Alton Junction. My work was all done, of course, and I was sleeping soundly when my wife woke me up to tell me of the horrible wreck. I jumped up and ran over to the place. There was nothing that I could do. Water would do no good, and so I stood looking on. I had started to stroll away when the explosion occurred. I intended going north to the Junction Station, but I had not run 70 feet away before I was knocked to my knees by the crash of the tank. I felt the hot oil light on my head and hands and felt the fearful burning sensation. To relieve myself I buried my head in the earth and threw dirt over my hands. Then I ran away. I don’t know how fast. Here at the junction I met a physician who bandaged my head and hand. Then they put me on my wrecking train and I came here. The sound wasn’t so loud as it was stunning. I didn’t look back much. All I wanted was to get away. The man that had charge of the switch at that place was a fellow by the name of R. Gratten. He kept a barber shop and attended the switch at the same time. The company hired him simply because he was cheap. I know that he has gone out of the country already, and they won’t find him soon. It’s a shame that a railroad company should be allowed hire men to do work in that manner, risking the lives of passengers, simply because it is cheap.”

Scenes at the Wreck

The scene at the wreck late in the afternoon was one of vast destruction. The burning oil had been thrown for a distance of 800 feet or more, and had set fire to two little cottages that stood facing the track. The little dwellings belong one to a man by the name of Jones and the other to Car Inspector Emery, of the Big Four. They could not be found, however, as they had gone to Alton with the hospital trains. On the track where the seven oil tanks had stood a line of melted, rusted car trucks and piles of ashes lay. Lying in a molten heap among them were the gnarled remnants of engine 109, and back of it the ashes of the four coaches with bars of twisted, protruding iron completed the side-track picture. To the east a wrecking train brought from East St. Louis lay, and to this the gang of wreckers carried whatever they saw fit to remove. The work of clearing the debris from the main track was soon accomplished, and trains plied to and fro at will. A small crowd of sightseers was gathered about the place, but always at a discreet distance from an oil tank that had not yet exploded, and which was credited with being perfectly empty. They plodded to and fro, each one bent upon gathering some little stick or piece of iron as a souvenir or memento of the great disaster. A little north of the station the bodies of the six dead lay in order awaiting the coming of the Coroner. One of these was identified by a watch upon his person which bore his name – Edward Miller. A singular feature of his death was that his watch stopped at 11:10, supposedly the time of the great explosion which buried him beneath a mass of heated iron. The telegraph operators and station employees generally were very cautious about their remarks. They professed ignorance of the number and names of the dead and the extent of the damage. Their orders, they said, were to keep still, and that if they talked, they were liable to lose their positions. The porter of the Wagner sleeping car that was attached to the train was found sitting morosely alone on a box near the station at Alton Junction. He refused to give his name, but the badge on his coat read “Wagner 474.” He said that the first knowledge he received of the calamity was when he was tossed over the back of a reclining chair and lay flat on the floor. He said the jolt was fearful and every body in the car was more or less tossed about. When the occupants recovered their feet and wits they hurried to the door. The oil from the tanks was already flowing toward the cars, a regular wave of flame, which gave little time for any one to leave in. Many of the passengers hurried away towards the station, fearing further trouble. “I did not stay long,” said the gentleman. “I knew there was goin’ to be more trouble, an’ so I just pulled off. I came down here and I didn’t go back nuther, nor I ain’t goin’. I’ve been in wrecks before, an’ I know enough to git out an’ away jist as far as the Lord’ull let me,” and with that, the porter lapsed into silence and refused to be disturbed by further questions. The station agent at Wann said that he thought the company had lost something like $300,000 by the fire. “The company won’t pay anything to all these sightseers who gathered about here to view the ruins. They have no business here, and, of course, if they come to grief, it is no fault of the company’s.”

A little north of the station the bodies of the six dead lay in order awaiting the coming of the Coroner. One of these was identified by a watch upon his person which bore his name – Edward Miller. A singular feature of his death was that his watch stopped at 11:10, supposedly the time of the great explosion which buried him beneath a mass of heated iron. The telegraph operators and station employees generally were very cautious about their remarks. They professed ignorance of the number and names of the dead and the extent of the damage. Their orders, they said, were to keep still, and that if they talked, they were liable to lose their positions. The porter of the Wagner sleeping car that was attached to the train was found sitting morosely alone on a box near the station at Alton Junction. He refused to give his name, but the badge on his coat read “Wagner 474.” He said that the first knowledge he received of the calamity was when he was tossed over the back of a reclining chair and lay flat on the floor. He said the jolt was fearful and every body in the car was more or less tossed about. When the occupants recovered their feet and wits they hurried to the door. The oil from the tanks was already flowing toward the cars, a regular wave of flame, which gave little time for any one to leave in. Many of the passengers hurried away towards the station, fearing further trouble. “I did not stay long,” said the gentleman. “I knew there was goin’ to be more trouble, an’ so I just pulled off. I came down here and I didn’t go back nuther, nor I ain’t goin’. I’ve been in wrecks before, an’ I know enough to git out an’ away jist as far as the Lord’ull let me,” and with that, the porter lapsed into silence and refused to be disturbed by further questions. The station agent at Wann said that he thought the company had lost something like $300,000 by the fire. “The company won’t pay anything to all these sightseers who gathered about here to view the ruins. They have no business here, and, of course, if they come to grief, it is no fault of the company’s.”

At Alton

In the City of Alton the news of the wreck was the topic of the hour. The streets there had the appearance of a county seat upon the arrival of some big circus. Everybody was out of doors. The streets were promenaded by the inhabitants; the store fronts were occupied by crowds of gossiping residents who collected together for the sole purpose of recounting the enormity of it and of recalling the great wrecks of the past. The depot station was the resort of another class who vaguely imagined that each incoming train would bear peculiar intelligence relative to the matter that might not be had elsewhere in the city. The offices of the local newspapers were scenes of vast activity, and the floors of the same were strewn with paper on which were scribbled more than a dozen introductions to the wreck. Sister Mary Joseph, the Mother Superior of St. Joseph’s Hospital, was one of the calm central figures around which a dozen excited assistants revolved with more or less rapidity, according to her directions. The sight of mutilated forms, while it stirred her heart into expressions of sincerest pity, failed to upset the goodly common sense and directing ability that characterized her every word. To a Globe-Democrat reporter, Mother Mary said: “We have dealt with the victims of wrecks before. They come to us very frequently, and we try to do all that human charity can do. This is not the first time that I have watched the incoming of wounded souls by scores. Two years ago there was a wreck, eight miles north of here, in which three were killed and some fifteen of the wounded were brought here. No. I have had experience and I give with all my heart to the suffering souls about me. I only trust that their pain will be less now than before.”

Some of the Witnesses

Among those who were witnesses to the explosion were J.L. Maupin and Robert Curdy, real estate men of Alton. Mr. Maupin, in company of J.H. McPike, was advancing toward the scene and was about 200 feet distant when the explosion occurred. The force of the shock for an instant turned them back and separated them. Mr. Maupin in relating his experience says:

“For a short while I made Nancy Hanks time in the opposite direction, but quick as I was, the flames overtook me and burned these holes you see in the back of my coat. As soon as the heat subsided sufficiently to admit it, I hurried to the scene and did all in my power to alleviate the sufferings of the victims. I saw a man running toward me in a sheet of flame. Just as he got to me he fell. Pulling out my knife I cut, as best I could, the blazing garments from off his body. When I had succeeded in extinguishing the flames, I stopped only long enough to ascertain that his name was Richardson, and then hurried on to assist the other unfortunates. In the meantime Robert Curdy and others were engaged at different points in their heroic efforts.”

Mr. Curdy said: “I think the force of the explosion must have spent itself in my direction. Although I was 600 feet distant when it occurred, the flames swept by me and passed in a sheet over my horse and rig, which were standing near. I can hardly describe the noise. It was not like a cannon, nor like thunder, but more like the rushing of a mighty force of air. Looking around me I saw boys and men running all directions through the fields.

Relieving His Sightless Friend

“One man headed toward me. I did not recognize him, but I called to him to stop, which he did. I had my knife in hand, and as he halted, I rushed up to him and cut and slashed away through a sheet of flame until there remained not a vestige of his original habillments. I tried with my voice to console him in his awful plight as with my hands I did what I could to alleviate his pain. He recognized my voice, and with his burned and sightless eyes turned toward me, he managed to inform me that he was my old friend, James Murray. In pulling off the sleeve of his coat, the skin of his hand stuck to it and came off like a glove, the nails with it. I threw dust over him and rolled him in the dirt. When I had extinguished the flames, little was there in that charred but breathing mass having any resemblance to James Murray. Others hurrying up took him in charge and, bundling him into a wagon, bore him to his home in Alton, where, I hear, he still lives.

“Over near the house, on the embankment and to the west of the scene of horror,” continued Mr. Curdy, “lay the smouldering remains of a boy of 14 or 15 years of age. It is supposed his name was Hagerman. I shouted to the fleeing ones to walk, not run, as running but fanned the flames. Hurrying on I overtook Willie McCarthy, a lad of 13. After I had done all I could for him, and with scarcely a bit of clothing left on him, he lay down and in his agony rolled over and over in the snow and ice. By this time the crowd of helpers had swelled considerably, and finding Mr. Maupin we jumped in the rig and whipped up toward Alton to secure increased medical attendance. To everyone we met we hastily communicated the sad intelligence of the second disaster and the dreadful plight of the victims. Houses were stripped of bed clothes, pillows and the like, and a multitude of tender and sympathetic care-takers was soon in attendance. On the road we met several doctors urging their steeds to the limit of endurance. In a short time after our arrival at Alton, every available physician was speeding on his errand of mercy.”

The News in St. Louis

General Western Agent W.F. Snyder, of the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway, whose headquarters are in Hurst’s Hotel, St. Louis, had but little information to give out concerning the holocaust near Alton. As soon as the collision took place the operator at Wann placed himself in communication with the main office of the Big Four system at Cincinnati, and the St. Louis office was “cut out” for a time. At 5 o’clock Mr. Snyder’s advices were that Engineer Webb had been killed and that in the subsequent explosion five men and a boy had lost their lives.

“The Big Four has been rather unfortunate of late,” said he, “though I can hardly see how the company can be blamed for the awful sequel to the collision. This morning I understood that the Southwestern Limited had stopped at the water tank opposite Wann Station, and that hot ashes and embers falling on a rivulet of oil that trickled from a single tank car on a siding had caused an explosion. Wann is a great transfer point, and five cars of oil are seldom left long in one spot. The station is about four miles back from the Mississippi River and gets its name from the Wanns, who were heavily interested in the old Indianapolis and St. Louis Railroad. Some three months ago two freight trains crashed together on a bridge near Terre Haute, Ind., pulling down a pier and costing the company about $85,000. I know of no St. Louis people hurt, and inasmuch as no passengers were injured, I have made no preparations for the reception of the wounded. The Southwestern Limited is a New York through train and our best one, though at this season traffic is not very heavy.”

Chief Dispatcher’s Advices

H.M. Stubblefield, Chief Train Dispatcher of the Big Four road in this city, was busy all day in the operating rooms at the Knapp building in St. Louis. When asked for a statement regarding the wreck he said, briefly: “Train No. 18, leaving the St. Louis Union Depot at 8:05 a.m., ran into an open switch at the west end of the Wann yards and collided with a number of oil tank cars. Engineer Webb Ross was killed and Fireman Dick White jumped and escaped. The engine and café car were destroyed. We do not know who left the switch open. About 11:40 o’clock some of the fire reached the tank cars, and five men and a boy who were standing by were killed. A wrecking train was sent at 9:30 o’clock.”

A Wreck in War Times

Two other memorable wrecks have occurred at Alton Junction, but in neither of the former were any deaths reported. The junction is built on the upper end of the great Sand Ridge and is the nearest point of the main line of the Big Four to Alton. A plug train from Alton joins the track at right angles, and the main line passes over Wood River and on up through the bluffs just above the town. In 1963 or 1864 the plug train had passed around a Y preparatory to proceeding on to Alton. It was supposed that the two trains could easily pass, but wrong signals caused a collision. The smaller train was turned over, but it is said only a few of the passengers sustained any bruises at all. Mike Bartlett, the conductor, escaped with a black eye.

A Serious Wreck in 1866

Later, however, in 1866, a more serious jump off occurred and the passengers were pretty badly shaken up generally. The engineer, fireman and baggagemaster, who resided in St. Louis, were badly injured, and the company lost considerable broken cars. Just below the junction where the tracks leave the Sand Ridge, the Big Four and Chicago and Alton Railways meet and run parallel to St. Louis. In those days, it is said, the trainmen of both roads took great delight in racing from the meeting point to the first stopping place, Long Lake. The Indianapolis and St. Louis of that date had been delayed for a few seconds at the water tank, and as the engineer neared the opening he heard the defiant whistle of the Chicago and Alton engine rounding the curve at Milton bridge. He probably put on all steam and started up a high speed, as he knew the lead of a few yards meant success in the race to Long Lake seven or eight miles below. In his hurry he no doubt failed to notice the open switch, which had been thrown to admit a gravel train to a sand pit on the left. The engine and train plunged on through the open switch and down through Hon. Z.B. Job’s meadow, a distance of at least 300 feet, before it was stopped by the soft ground. The engine and baggage car careened, but the occupants had jumped before the ditch was reached. The passenger cars and the occupants were badly shaken up, but none of the passengers, it seems, were badly hurt. John J. Snowball, the Assistant Roadmaster, conveyed the injured men to Alton, and other employees hauled the passenger cars back on the track. The baggage car was burned and the engine was a total loss, and remained many months in the place where it fell. The news of the accident then, as now, caused the people of Alton, Bethalto, and the farmers of the surrounding country to flock to the scene in great numbers. Even long after the wreck had been cleared away the old settlers would spend long hours in relating the great story of how an engine and a train had crossed Job’s pasture from the Indianapolis and St. Louis and finally jumped on the other track.

A Conductor on the Explosion.

The reports that reached the Union Depot last night of the horrible wreck were very confusing. Some placed the loss at fifty lives, with almost 100 injured, while others placed the loss at only one killed and about six injured. James H. McClintock, a conductor on the Big Four, was an eye-witness of the explosion. When seen at the depot last night by a Globe-Democrat reporter, he said:

“We arrived at Wann Junction on our westward trip about 11:30 o’clock. We then heard of the wreck, which had occurred about 9 o’clock. Webb Ross, the engineer, was the only one reported killed. The cars and oil tanks were then burning only a few blocks away. I was standing on the platform viewing the destruction, when all of a sudden an explosion shook the very ground beneath my feet and rattled the windows in the station. There were hundreds of people standing near, and as a sheet of flame shot into the air over 100 feet high, the crowd attempted to escape. Before they had moved any distance to speak of the burning mass of oil came down on them. Shrieks of agony, groans and stifled cries met our ears with a sickening effect. Pell mell scattered the human beings, bereft of all feelings, only endeavoring to get out of reach of a fiery death. Those caught in the burning mass must have perished immediately. People came running in all directions without a shred of clothing on their persons, the fiery liquid having done its work only too well. Their hair singed to a crisp and their bodies a mass of blisters, the wretches presented a heart-rending sight. Taken all together, it was the most awful sight that was ever pictured. It was a scene impossible to describe. I remember one little boy 13 years old who ran into the depot utterly naked and crawled under the benches frantic with fear. All blistered as he was, he unhesitatingly asked an anxious gazer to bring a priest. There was none around, and the boy half smiled, closed his eyes and lapsed into unconsciousness. In a spectacular sense the explosion was one of the grandest sights man ever witnessed. Fireworks were never invented which cast such a pretty reflection in the sky as did the burning oil on this disastrous occasion.”

Grief at East St. Louis

When the news of the frightful accident at Alton Junction reached East St. Louis yesterday hundreds of people flocked to the Relay Depot, telephone and telegraph offices to learn if any of their relatives or friends were among the dead or wounded. Many mothers and wives whose husbands were employees of the Big Four ran from place to place wringing their hands and giving vent to their great distress, as during the great excitement no definite information could be obtained. Scores of the immediate friends of ex-Alderman Patrick Vaughan, who, next to poor Ross, is the oldest engineer on the road, haunted the Big Four years. Mr. Vaughan, however, it was learned, had just passed Wann, and the train following had met with the mishap. Then again it was rumored that George Kirby, another engineer of the road and highly respected citizen of East St. Louis, was at the throttle of the ill-fated engine. Finally, when the facts were wired, the friends of all engineers but Ross and those of Timothy Houlihan, the fireman who was injured, returned to their usual business.

Ross was well known in East St. Louis. He had a regular run on the Cairo Short Line, the southern division of the Indianapolis and St. Louis, which now forms a part of the Big Four, and resided for many years in the southern part of the city. As he spent more time at Bloomington than in East St. Louis he removed to that city several years ago. The scene at the depot was one which will be remembered by all who witnessed it. Seldom has such a demonstration of grief on the part of the people been noticed. From some cause only meager news from the place could be obtained, and the lack of information seemed to play upon those present. Many imagined that friends were purposely withholding the facts of a death, and pleaded with everyone about the Relay Depot for the names of those who had met their death.