Radio Articles

Garry Moore’s Early Days In St. Louis

Unless you’re a fan of trivia, you may not realize that Garry Moore once did a stint as a radio staff announcer here in St. Louis. His name was different then, and his goals didn’t exactly envision the new medium – television – which would make him famous.

Thomas Garrison Morfitt was born in Baltimore January 31, 1915. As he grew up he was able to witness the development of the exciting new entertainment medium called radio. Morfitt was convinced he could be a part of it. He worked selling ties in a local department store during the day and spent his evenings writing radio scripts, which he would try to “sell” during his lunch hours, hawking them to owners of local stations.

“I always wrote a strong part of the script for myself,” he told Jack Carney on KMOX in 1979. “Finally, one of the radio managers said to me ‘Look kid. You’re a lousy actor, but you write pretty well.’” Moore was given a job as a writer.

It was the sort of job that offered plenty of opportunities, including the one Morfitt had been hoping for: “You got into all sorts of things. You wrote mysteries, shows, advertising, spot announcements. I wrote the jokes for a daily one-hour variety show. It was emceed by an ex-Vaudevillian brought down from New York. And then, just like a bad ‘B’ movie, he got ill one day and the station manager came to me and said, ‘Listen, you’ve been writing this junk. You may as well get up there and read it.’ The emcee turned out to be terminally ill and I inherited the job.”

Morfitt admitted to Carney that he had no delusions of his ability as an entertainer. “I had always wanted to be an actor, but the show was very successful. After I’d been there about 2 1/2 years, I guess, I began looking around for other pastures where I could be an actor, or at least something more important than an entertainer. I sent demo discs around to several radio stations, and one of them was KWK in St. Louis.”

In the 1930s radio was maturing as an entertainment medium, and when KWK made an offer, Morfitt accepted. “I went out there principally as a special events man because my forte turned out to be ad-libbing. While I was in Baltimore I used to do a lot of things like call the horse races – whatever called for extemporaneous chatter. So I went off to St. Louis in that capacity.”

Once again, Thomas Garrison Morfitt’s plans for the future got sidetracked.

“Then they decided that they wanted an afternoon variety show just like the one I had fled in Baltimore. They told me they wanted me to do it and I told them I wasn’t very good at it. They said ‘That’s not what we hear from Baltimore.’ The program they gave me had the magnificent name of ‘Mid-Afternoon Madness,’ and I kept telling them I was no good at this kind of thing.”

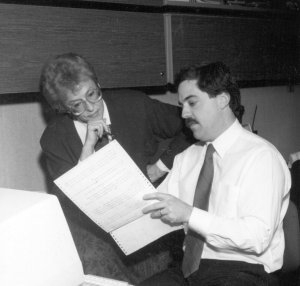

Thomas Garrison Morfit (Garry Moore) in Piano

Morfitt was getting depressed at the way things were going at KWK. “I started sending out resumes and I had already had some interest expressed by WLW in Cincinnati. But to show you how fate can randomly step into your life, there happened to be a man from NBC in Chicago who was just passing through St. Louis. While he was at his hotel he turned his radio on and heard this afternoon show I was doing. At that time up in Chicago they were in need of an emcee. Next thing I know I get a call from NBC asking me to send them a demo record, which I did, and the next thing I know, I’m on a network show based in Chicago, much to my surprise. And I’m still doing this thing I thought I was no good at, but I thought, ‘Well, if they want to pay me this much money to do something I don’t think I do very well, why should I argue?’”

Fate, and a little effort on his part, provided the next step for Morfitt. “When my vacation time came I went to NBC in New York. They transferred me from Chicago and put me on the same kind of a show. So the only difference was that I was based in New York.” He was 25 years old at the time.

One thing led to another. Garry Moore was paired with Jimmy Durante on the “Comedy Caravan,” which gave both of them much-needed nighttime radio exposure. He went over to television in 1950, doing a daytime variety show for eight years. It was during that stint that a pair of producers came to him and proposed an emcee slot for him on a nighttime game show they were pitching. It was called “I’ve Got A Secret.”

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 4/2000)