Radio Articles

They’re Frank and Ernest – But Not Really

by Yanner Alexander

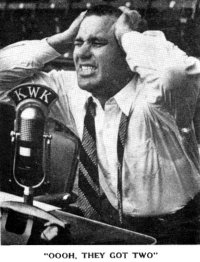

and Ernest, bottom

Bob Thomas’ favorite flavor is chocolate…Danny Seyforth takes vanilla. Those are the only differences between KWK’s Frank and Ernest.

Danny is Frank and Bob is Ernest. They met when Bob was announcing one of Danny’s programs about three years ago, January, 1930. Danny stopped by the studio to renew the friendship. Danny started playing the piano…Bob aired his tenor…they traded gags…and a new act was born.

Their audition was a success, but on the day set for their first broadcast, Danny took sick – grippe – and it was postponed. Then the habit of doing the same thing began with Bob developing the symptoms, and the debut was set ahead another week.

The false starts didn’t mean anything. When they did get going they clicked immediately. The original schedule of two broadcasts a week was increased to three, and then to every weekday.

There’s no professional jealousy, that bugaboo of so many successful teams. When Danny hits a false note, it doesn’t happen often, but Danny’s not perfect – Bob doesn’t beef about it afterwards. If Bob makes a mistake – silence again.

Bob prepares Monday’s jokes and Tuesday’s riddles and they collaborate on the Saturday playettes. Danny creates Margie and her mother on Wednesday and selects the old favorite tunes and poems for Thursday and Friday. He also does all the musical programs as Bob’s sports announcing keeps him pretty busy.

For the past two years they have been going south in the spring with the Cardinals and with Bob’s father, Thomas Patrick Convey, president of KWK. They trek along with the ball club and barnstorm all the radio stations along the route. Helps build up their names and fame, and, incidentally, gives Bob and opportunity to get acquainted with the ball club over again in preparation for his sports announcing.

Bob’s five feet nine and 160 pounds, light brown hair, hazel eyes. Danny’s a smaller, darker edition. He wears his moustache on a schedule. He shaved it off for three months because Bob didn’t like it. Now he’s starting it again for another three months. Danny carries an art gum eraser around with him to keep his black and white sports shoes clean. Bob has a passion for singing lead in a trio or quartet. Any time he sees one in a practice session, he joins it, and is immensely proud of himself if he succeeds in carrying the tenor well.

They use the same desk, officially Bob is Robert Thomas Convey, vice president of KWK. They don’t borrow one another’s ties, which may be one reason they never quarrel. But they have sweaters to match and generally buy the same sort of clothes. They both play golf, although Bob goes around in the early eighties and Danny’s score sometimes looks more like a batting average. They swim, too, at the Convey summer home in Kirkwood, where Danny spends most of his time. They like the same type of girl. Blonde or brunette not specified, but no girlish gigglers, please! When they order dinner, it’s just a repetition of “I’ll take the same,” until it comes to the ice cream.

(Originally published in RAE, 6/18/1932)

Harmony Duo Now Heard On Old Judge And Norge Programs

Unceasing in their efforts in search for new radio talent through various sources, the Program Department of Station KWK discovered Frank and Ernest – that well known comedy and harmony team who recently celebrated their 200th broadcast after having been on the air for the past ten months. Always on the alert for a new feature, the Program Department immediately recognized in these two young men the ability which they possess. The Department’s confidence has not been betrayed as this team of popular entertainers is now being featured on the David G. Evans Coffee Company program as well as the Norge Company program.

This team is endowed with the ability and talent, and before many months these young men should appear as brilliant stars on the radio horizon.

“Wonderful, magnificent!” exclaims the radio listener as the strains of the theme song of the Norge Company of Missouri filter through the loudspeaker. These programs are heard Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Saturday evenings over KWK.

Featured in these broadcasts is the Viking Orchestra, composed of sixteen of the leading musicians in St. Louis. The guest artists on these programs consist of a baritone, tenor, a blues trio and a harmony comedy team.

KWK is to be complimented on these programs as they embody everything musically from grand opera to jazz with the result that these presentations are becoming the most popular on that station.

(Originally published in Radio and Entertainment 12/26/1931).

KWK Introduces World’s Youngest Radio Announcer

KWK has the world’s youngest radio announcer. He is 5 years old. His name is Don Cosby and he is the son of Clarence Cosby (general manager of the station).

Last week the baby announcer officiated as master of ceremonies during the broadcast of the Frank and Ernest program, a regular feature at the station. He introduced the program, announced the numbers and closed it, with all the flourish and confidence of a regular announcer.

During the program his mother and father and members of the studio staff watched from the spectators’ section of the studio.

(Originally published in Radio and Entertainment 6/11/1932).