THE GLOBE-DEMOCRAT’S GOLDEN CENTURY

Story of newspaper is an absorbing one of outstanding personalities conscientiously performing a public trust

by Robert Willier

St. Louis in the 1850’s was not the calm. deliberate, orderly city it is today. Its 80,000 residents, confined largely to an area bordered on the west by today’s Eighteenth street, were a composite of English, French, Irish and German – frontiersmen, aggressive, energetic, impatient.

From varied backgrounds, faced with the common struggle of creating a new life under great hardships, they tended to disagree violently on many things, notably politics.

Mob violence was not uncommon; indeed, Mayor Kennett’s election on Apr. 5, 1852, was attended by a riot which involved most of the city, resulted in one death and the destruction of numerous houses. One section of the mob, not content with small arms, obtained two brass six-pounders from the armory and fixed them in position “so as to sweep with murderous certainty either side of Second street, on either side of which were immense crowds of Germans.”

True, St. Louis was not the raucous life of Gold Rush towns, but living here at mid-century was at least rugged, filled with dynamic atmosphere of competition, of conflicting ideas and of differences normally arising from a melting pot of many races, creeds and backgrounds suddenly thrown together. To add to the confusion, there was a constant flow of people to the West, through this gateway, the “jumping off point” of the early settlers.

There was one unifying influence – the press. Just as Colonial America had early realized the need for a communications medium – Benjamin Harris, an exiled English newspaper editor, having issued his “Publick Occurrences Both Foreign and Domestick” in Boston on Sept. 25, 1690 – so early St. Louis found comfort in its first paper, the “Missouri Gazette,” issued July 12, 1808, the first newspaper ever published west of the Mississippi.

Seven years later an “opposition” paper, the “Western Journal” appeared, and from then on till mid-century there were numerous journals, “Enquirer,” “Beacon,” “Herald,” “People’s Organ and Reveille,” to name but a few. These all had their effect as a means of bringing issues into focus and in generating public opinion. Mortality of the papers was high, however, reflecting the problems of publishing and, to a certain extent, the fact that the papers were “one-man” operations.

From the 1850’s on, the pattern of journalism became more fixed, particularly in the morning field. The “Democrat,” for example, established in 1852, has had an unbroken history of 100 years. It became the “Globe-Democrat” in 1875 and has continued under that name to the present.

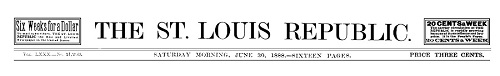

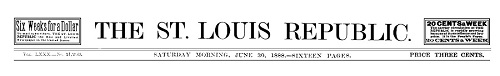

In the evening newspaper field, the “Globe-Democrat’s” contemporary today, the “Post-Dispatch,” emerged under its present name in 1878. (Joseph Pulitzer purchased the “Dispatch” at public auction in front of the Old Courthouse in December of the same year, the price – $2500.) Just as its ancestry might be traced to July 3, 1838, with the founding of the “St. Louis Evening Gazette,” later to become the “Dispatch,” so the “Globe-Democrat,” which acquired the “St. Louis Republic” in 1919, could claim ancestry back to 1808, since the predecessor of the “Republic” was the “Morning Gazette.”

That only one morning and one evening newspaper eventually should survive in St. Louis is not out of the ordinary. Alfred M. Lee, in his history of American journalism, pointed out that there have been some 16,000 dailies launched in the United States since 1783. By 1952 there were only 1873 dailies left out of the 16,000. This high mortality rate, accentuated in recent years, is mute evidence of the many problems, including constantly increasing costs, of publishing daily newspapers today.

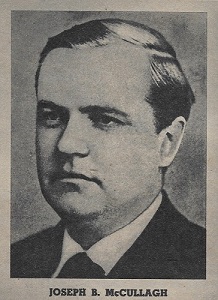

Inevitably those who today can recall the “Globe-Democrat” before 1900, do so with chief reference to a personality known as “Little Mack” – editor Joseph B. McCullagh. Like other great editors, publishers or proprietors of the paper, McCullagh helped shape metropolitan St. Louis’ destiny.

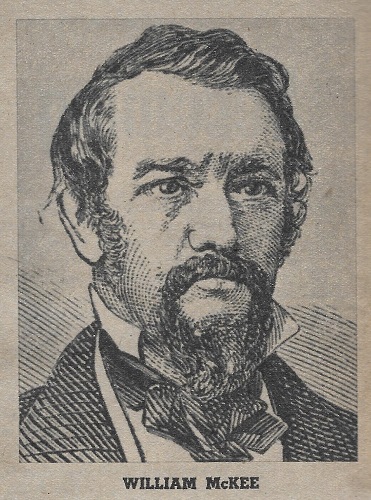

But the man who began the “Democrat” (of today’s “Globe-Democrat”) was William McKee, who entered the field of journalism as owner of a paper called the “Barnburner,” in which his anti-slavery sentiments were strongly expressed. It was McKee’s “Barnburner,” its name changed to “Signal,” which became the “Democrat” in 1852, and which was strengthened by the addition of the “Union” a year later.

McKee was not unaware of the dangers of voicing unpopular sentiments of criticism, especially in a city which was Southern in character and politically Democratic. The proprietor of the “Union” (under its new name of “Argus”), one Andrew Jackson Davis, was assaulted on the street by an irate reader “in such a manner that he died a day or two later.” The assailant was tried, convicted and fined $500.

With the aid of his associates. B. Gratz Brown and Francis P. Blair, McKee hammered away on the anti-slavery theme, despite the antagonism it created in this border state. To say the campaign had repercussions, especially in profits, is to put it mildly since it took some seven years for the company to pay off its $15,000 debt for the purchase of the “Union.”

Under McKee’s leadership the “Democrat” swung its weight behind Lincoln, McKee himself having been influential in obtaining Lincoln’s nomination. The “Democrat” fought so vigorously against secession that the Great Emancipator said it had done more “to preserve the Union than 20 regiments.” But the “Democrat’s” stand was often assailed, mobs collecting at the “Democrat” building to demand a change. Soldiers from the armory had to be called to break up these mobs. McKee would give no ground; indeed, if anything he guided the paper’s writers (he wrote very little himself) into stronger reiteration of their stand.

Following the Civil War the “Democrat” flourished under the guidance of McKee and his partners, Daniel M. Houser and George W. Fishback. Houser, who had been with McKee in earlier newspaper ventures, was the mastermind of the business office. It was he and McKee who agreed to hire a high-priced editor named McCullagh in 1871, a man who had gained a national reputation as a war correspondent covering the campaign of Gen. Grant.

This step and others not to the liking of Fishback resulted in a dissolution of the partnership, with the “Democrat” being sold to Fishback for $456,100. Within a matter of months the team of McKee and Houser were back in business with a paper they named the “Globe,” and within a year they had McCullagh as their editor.

The competition of three morning dailies (Republic, Globe and Democrat) was too much for the “Democrat.” McKee and Houser, now aided by a third associate whose family name is familiar, a nephew of McKee, Simeone Ray, bought it for $125,000 less than Fishback had paid for it.

“Little Mack,” the new managing editor of the “Globe-Democrat,” the man who had come to American from Dublin at 11 and who started as a compositor on the “St. Louis Christian Advocate” in 1858, was at last in his element. The “Globe-Democrat” was his only love. He lived it day and night.

A bachelor, short and somewhat stout, but with an impressive hard-boiled demeanor, McCullagh made newspaper history. The newspaper interview, with public figures permitting direct quotations – Little Mack invented it. The short, pungent, one-sentence paragraph – he is said to have originated it. The use of complete wire service – McCullagh used so much the “Globe-Democrat” became famous as the largest wire service newspaper outside New York and Little Mack found himself immortalized by Eugene Field in a poem that ends:

“From Africa’s sunny fountains and Siloam’s shady rills,

He gathers in his telegrams and Houser pays the bills.”

First and foremost, McCullagh was a great reporter, with a sense of news and timing, based upon his own wide experience, that kept his staff scurrying at top speed. He knew what to expect of reporters and they of him, especially after they read his 48 points for good reporting.

As editor, however, Little Mack truly hit his stride. His crusading spirit was an invigorating element in the ‘80s and ‘90s, perhaps unequalled in St. Louis’ history. Why, he asked, was St. Louis so slow in railroad development and service? He began a campaign, sent reporters into the Southwest to show the developments resulting from railroad service; he opened his own railroad department; he editorialized.

As editor, however, Little Mack truly hit his stride. His crusading spirit was an invigorating element in the ‘80s and ‘90s, perhaps unequalled in St. Louis’ history. Why, he asked, was St. Louis so slow in railroad development and service? He began a campaign, sent reporters into the Southwest to show the developments resulting from railroad service; he opened his own railroad department; he editorialized.

Ably assisted by Daniel Houser, who succeeded McKee as president, he even financed the first fast mail services for St. Louis.

In many other ways he “boomed” metropolitan St. Louis, being credited, incidentally, with originating the word “booming.” To reward him for his efforts, a group of citizens offered him $25,000 to purchase a residence, but, he declined the offer for fear “they might come around later and try to run the paper.”

McCullagh dared match editorial swords with anyone. He is quoted as saying on one occasion “why use a barrel of vinegar when a couple drops of prussic acid will do the job?” Among his most noted campaigns was the one in 1878-79, now referred to as the “gambler’s roundup.”

Gambling had become big business, being afforded police protection through bribery. McCullagh saw it as a blight upon the city, the “cause of suicides, embezzlements and thefts to cover gambling losses.” Only an aroused public opinion, he determined, could force the cleanup required.

The public did become aroused as a result of the “Globe-Democrat’s” articles, features and editorials. A grand jury was impaneled with McCullagh as foreman. A new anti-gambling law was rushed through the State Legislature. And the gambling ring, together with its kingpins, was effectively smashed.

Before the turn of the century the “Globe-Democrat” had established its niche in the newspaper field in metropolitan St. Louis. It was a “world” paper, proudly printing on its front page a map and slogan “All the News of All the Earth.” By wire and special correspondents the paper brought to its readers a wealth of information from all parts of the globe.

This, of course, was in striking contrast to earlier journalism here since, before the telegraph in St. Louis (1849) news was primarily local and personal. But the “Globe-Democrat” realized the avid interest of readers in things “foreign and domestic,” surpassed all other papers in producing the world-wide coverage desired.

In 1897, on a single Sunday in July the “Globe-Democrat” printed 65,000 words of telegraphed copy in addition to 35,000 words of Associated Press telegraphed copy. Here, for example, are a few typical headlines from the front page on Jan. 1, 1909: Gloom in England, telling of Great Britain’s “miscalculation and disaster” in South Africa; Germany Objects, a story about German protests over the seizure of one of their mail steamers by the British; Bomb Plot Foiled in Manilla; and Naval Officers Disturbed (Dateline: Washington), because some Navy order automatically gave special privilege to certain officers while others had to use the “regular red tape method” of getting the same privilege.

These stories and others from outside the city occupied over 80 per cent of the front page. While this percentage of “national” vs. “local” news did not hold throughout the rest of the paper, there is no doubt that the editorial policy was to give weight to the national and international news the subscribers wanted to read.

In later years this policy has been modified only to the extent of providing a more even balance of news, with emphasis naturally shifting as events justify. By gradual evolution the “Globe-Democrat” has adapted itself to its geographical area – the “49th State” – to the likes of morning newspaper readers, to the effect of new means of communications – radio and television – and has emerged with increasing circulation, prestige and influence.

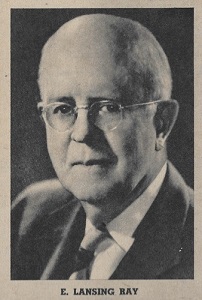

The opening of the Twentieth Century marked the beginning of an era in which one personality – E. Lansing Ray – stands out above all others in the “Globe-Democrat’s” second 50 years. While he did not officially take the helm until 1918, he was on his way up through the ranks starting in 1903.

Like McKee in the first 50 years, Ray has proved to be a man capable of great leadership without personally intruding himself into the limelight of publicity. The paper he has directed for so many years is living evidence of his ability and personality.

His personal antipathy toward the limelight has tended somewhat to restrain the paper from extravagant claims and back-patting. The test of the paper, as he has viewed it, has been the paper itself, day by day, the kind of job it was doing, the service it was rendering its community and readers.

Avoiding unnecessary controversy, the “Globe-Democrat” has nonetheless been a constant source of information about important issues and needs of this area. For example, it can point to numerous articles and editorials advocating smoke elimination. But the paper makes no claim to having single-handedly cleared the city of smoke. It is content to say it did its share.

As is well known, a paper’s editorials are the reflection of opinions and policies of the publisher. Examination of American journalism shows the widest possible divergence of editorials as might be expected. Biting, sarcastic, controversial, liberal, conservative, instructive – take your choice and you find successful papers which regularly use one or more of these types.

For the “Globe-Democrat,” since the acquisition of the “Republic,” the policy has been non-partisan, instructive, interpretive and reflective. The publisher on several occasions has explained that he does not approve the paper “dictating to or lecturing” on every subject. Except on major issues the paper prefers to let readers make up their own minds after presenting factual news coverage and editorial material of interest and value.

The value of this approach can be seen in the Pulitzer Prize winning editorial this year, an editorial entitled “The Low Estate of Public Morals,” written by Lou La Coss, “Globe-Democrat” staff member since 1924 and editor of the editorial page since 1941. La Coss, a journalist of national renown, has invigorated the paper’s editorial page, added to its influence and prestige.

A review of the “Globe-Democrat’s” editorials in recent years shows it has spoken out vigorously on major issues. And in the beginning of its second century there may be anticipated an increasing tempo of aggressive editorials because the publisher views these as critical times in our national history – critical in the same sense as McKee viewed the pre-Civil War era, as McCullagh viewed the post-Civil War era.

At the turn of the century, following McCullagh’s death, the “Globe-Democrat’s” managing editor was Capt. Henry King, whose contribution to St. Louis journalism rests chiefly on his development of a well-rounded paper – in news, features, society, sports, financial and editorial. He believed in giving readers their money’s worth, a Sunday edition, for example, consisting of four parts: I and II of news, III features, and IV sports and society.

One Sunday chosen at random in the files in 1900 showed the feature section containing stories on the Holy Year, Part II of a serial by Bret Harte, and an intriguingly intimate story on the home life of Queen Victoria. This section, as well as the entire paper, contained an excellent representation of advertising by national and local concerns.

Typical of the writing was an editorial referring to Gov. Lon B. Stevens as the “sapient son of a sainted sire,” and another which said “the police are so deeply occupied assessing the force and making presents to the Police Board that reports of burglaries annoy them.”

As might be expected, there was a great rivalry between the “Globe-Democrat” and the “Republic.” These morning dailies usually ended up on different sides of the political fence, and not as their names would indicate. For the most part, the “Republic” favored the Democratic party while the “Globe-Democrat” was strongly Republican.

When it is recalled that the rivalry of these two papers began in 1852, that the “Republic” in its last decade was owned principally by one of St. Louis’ most representative citizens, David R. Francis, and that the “Republic” represented a direct line of journalistic practice to the very beginnings of the city, some idea can be gained of the problem that faced President Ray when the “Republic” was purchased in 1919.

When it is recalled that the rivalry of these two papers began in 1852, that the “Republic” in its last decade was owned principally by one of St. Louis’ most representative citizens, David R. Francis, and that the “Republic” represented a direct line of journalistic practice to the very beginnings of the city, some idea can be gained of the problem that faced President Ray when the “Republic” was purchased in 1919.

The physical absorption was easy, for a newspaper is not a building, brick and steel and concrete, as Francis had learned when he poured hundreds of thousands of dollars of his own money into an effort to find a “formula” to make the paper successful.

The problem was personality – the personality of the “Republic.” For every newspaper worthy of the name is a living, breathing personality, as full of character and moral fiber as the men who run it, who are its reporters, its salesmen, its editors. Great newspapers, reflecting great editors and staffs, have been published from physical surroundings that were little more than a printing shop. But in the language, the makeup, the “faithfulness of their public trust” these papers were the mirrors of great journalists.

To absorb one personality within another is a real problem, and Publisher Ray solved it in a manner that has proved its effectiveness through succeeding years. Ray, through his editorial page editor , Casper Yost, proclaimed the paper now to be no longer politically partisan: “The Globe-Democrat is an independent newspaper, printing the news impartially, supporting what it believes to be right, and opposing what it believes to be wrong, without regard to party politics.” This statement of policy has appeared on the masthead of the “Globe-Democrat” every day since that time.

Eliminating political partisanship did not, of course, infer that the paper would not editorially support candidates it considered best for public office. Nor did it mean the paper would not editorially support or criticize policies of either party. The paper has indorsed candidates and policies as its conscience dictated in the best interest of the city, state and nation without regard to party affiliation.

The “Globe-Democrat,” which had opposed President Wilson as a candidate, surprised its readers by supporting President Wilson’s war policies and his League of Nations, while newspapers all over the country were objecting to his “high-handed” procedure. In other ways the “Globe-Democrat” gained stature with its readers by its honest efforts, as the only morning paper, to produce a highly readable, interesting, entertaining and reliable publication.

The “Globe-Democrat,” which had opposed President Wilson as a candidate, surprised its readers by supporting President Wilson’s war policies and his League of Nations, while newspapers all over the country were objecting to his “high-handed” procedure. In other ways the “Globe-Democrat” gained stature with its readers by its honest efforts, as the only morning paper, to produce a highly readable, interesting, entertaining and reliable publication.

On the retirement of Capt. King in 1915, Ray, then secretary of the company, was instrumental in establishing a change in policy which has governed the reporting and interpretation of news since that time. He divorced the editorial page and the news departments, establishing each as a separate unit. Henceforth the editorial page, through its own editor, reflected the policies and thinking of the publisher while the news department, under the managing editor, handled the news.

Another “Mack,” this time a noted reporter-editor, Joseph McAuliffe, was installed as managing editor. He was succeeded in 1941 by the present managing editor, Lon M. Burrowes. Burrowes and McAuliffe joined the “Globe-Democrat” on the same day in 1913 and, at the time the change in managing editors was made in 1915, McAuliffe was city editor and Burrowes telegraph editor. Later Burrowes became news editor, directly under McAuliffe, and was ready to step in and maintain the continuity or direction which has extended for more than 35 years.

Casper Yost, then Sunday editor, became the first editor of the editorial page and was succeeded in 1941 by Louis La Coss, veteran news, feature and special editorial writer.

On the “publishing side,” the continuity has existed the full 100 years of the paper. Sons of Dan Houser – W.M. Houser and D.B. Houser – and a grandson, W.C. Houser, have held executive positions down through the years. Charles H. McKee, nephew of one of the founders, was president of the paper for a period. And, of course, the present publisher is a son of Simeon Ray, nephew of William McKee, one of the founders.

The sequence received a tragic blow shortly after World War II with the death, at age 35, of E. Lansing Ray, Jr., who was to have succeeded his father. Young Ray came to the paper in 1932 and, until he was called into service in 1941, had trained for the day that he would become publisher by working in virtually every department of the newspaper. In his early days he rode delivery trucks, sold ads, acted as a reporter – following fires and the Cardinals, covering Jefferson City and the local news front.

With this sound background, he moved into the executive branch of the business and was associate publisher and secretary at the time of his death in 1946.

Young Lansing, a popular and active figure among the city’s junior executive group, had been president of the Advertising Club and prominent in other civic activities prior to being called into service.

During World War II he served with highest distinction as an officer in the Army Intelligence Corps. He was awarded the Legion of Merit for “exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding service in the Mediterranean theater of operations” and was cited for setting up the counter-intelligence network in that area. He was invalided home in 1944 and, when discharged from the Army in March, 1945, held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

When E. Lansing Ray, Jr., died in 1946, the logical choice for succession within the family circle became James C. Burkham, a nephew of the publisher. Like young Ray, Burkham had learned the business from the ground up. He had just about completed this training when he, too, was called into service in 1942. Like Lansing Jr., Burkham was also detailed to the Counter-Intelligence Corps of the Army.

Upon return from the service he moved into the executive ranks at the “Globe-Democrat” and immediately displayed the qualities and love and understanding of the publishing business which Ray Sr. was seeking. Burkham became president of the company in 1949, with Ray retaining his three-way position of publisher, editor and chairman of the board.

Honors and high positions have come to many “Globe-Democrat” personnel through the years. It was the training ground for such men as Eugene Field, Capt. John H. Bowen, Henry M. Stanley (the explorer), John Hay, Myron T. Herrick and John G. Nicolay.

Publisher Ray, who was for many years a curator of the University of Missouri, has received many honors but values most his distinction of having been for 29 years a director of the Associated Press.Only four men in the whole history of the AP had served longer as a director, when Ray retired in 1951. During that period he served two terms as first vice president. Another distinction he values is that of having been one of the small handful of St. Louisans who backed Lindbergh in his historic flight.

Publisher Ray, who was for many years a curator of the University of Missouri, has received many honors but values most his distinction of having been for 29 years a director of the Associated Press.Only four men in the whole history of the AP had served longer as a director, when Ray retired in 1951. During that period he served two terms as first vice president. Another distinction he values is that of having been one of the small handful of St. Louisans who backed Lindbergh in his historic flight.

Not particularly enthusiastic about flying himself, Ray nevertheless had made certain that the “Globe-Democrat” was in the forefront of aviation promotion. In it he saw the significance that McKee and “Little Mack” had seen in the coming of railroads during the “Globe-Democrat’s” first half-century. So the prospect of demonstrating the Atlantic could be flown non-stop, plus the prospect of bringing credit to St. Louis if the flight were successful, was a “natural” for Ray.

The “Globe-Democrat’s” interest in making St. Louis an important air center has continued through the years. Immediately after World War II, for example, the “Globe-Democrat’s” front-page reports on the condition of Lambert Field, including the reference to “more wind and words than concrete,” were credited with stimulating improvements which have kept the city very prominently in the world aviation picture.

Ray’s civic interest has caused the “Globe-Democrat” to sponsor a year-round program of community projects of interest not alone in St. Louis but to the whole 49th State.

These projects embrace a wide range of interests, but if there is any preponderance it is to the attention given to children and to youth. Quizdown, soon to be replaced by a Spelling Bee, and the High School Revues – both co-sponsored by Radio Station KWK, in which the “Globe-Democrat” owns a minority interest – are designed for elementary and high school students. The annual Soap Box Derby interests boys from 11 to 16, while the Golden Gloves, probably the most popular of all “Globe-Democrat” promotions, provides healthful training and good sport for hundreds of young men from 13 years of age on up, every year.

Among the most recent “Globe-Democrat” public service projects are two which have developed tremendous interest, both among participants and among the general public of the 49th State. They are the annual Christmas Choral Pageant and the Missouri Soil Conservation Awards program.

When the St. Louis Community Chest Fund of 1930 failed by over $50,000 to reach its goal, the “Globe-Democrat” guaranteed that amount, then put on a campaign that carried it over the top.

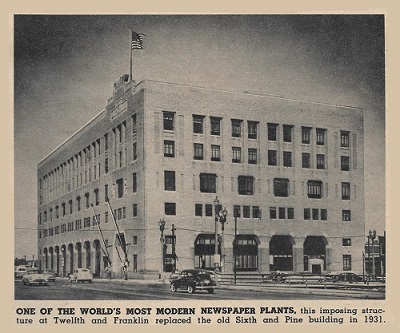

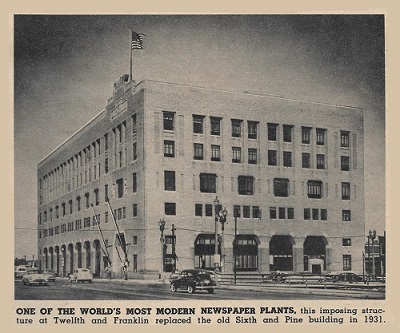

Now in its fourth building in a century, the “Globe-Democrat has production facilities which are a far cry from the old Ramage press that did well to produce 200 “Missouri Gazettes” a day. But the intricate machinery and methods of today’s modern newspaper plant are not as impressive to the reader as the single paper he gets each morning – its appearance and content.

Now in its fourth building in a century, the “Globe-Democrat has production facilities which are a far cry from the old Ramage press that did well to produce 200 “Missouri Gazettes” a day. But the intricate machinery and methods of today’s modern newspaper plant are not as impressive to the reader as the single paper he gets each morning – its appearance and content.

To make reading easier, the “Globe-Democrat” a few years ago changed to a style of type face and make-up considered by experts to be among the best there is today. They are easy on the eye and easy for the reader who must get his news in a hurry. Furthermore, the “Globe-Democrat” eliminated the “jump-over” from Page 1, being one of the first papers in the country to do so.

For its Sunday readers the “Globe-Democrat” provides, in addition to its regular sections and comics, three “supplements” known respectively as “This Week,” “American Weekly” and “Globe-Democrat Magazine,” a veritable department store of reading matter.

The area served by the “Globe-Democrat” in 1952 is a far cry from that in 1852. Today the paper provides the only morning newspaper in a metropolitan district of 1,681,300 people. By actual survey, however, the paper’s influence and readership encompass a much larger area, known as the “49th State,” which has a population of over 3,384,000.

In serving this great industrial area of the heartland of the Mississippi Valley, the “Globe-Democrat,” ending its first century, and Publisher Ray, nearing a half century of service, can be certain this morning daily newspaper is progressing, is doing its utmost for its readers. It is, therefore, fulfilling its public trust.

In many parts of the world, the lights have gone out on a free press. Argentina, China, Czechoslovakia, Poland, the list goes on endlessly of countries where dictators or Communists control the press to their own ends.

At least half the world’s population today knows nothing but what their government wants them to know. They are spoon-fed the propaganda by radio and the press, that keeps them servile, subservient.

But here in America, here in St. Louis, we have freedom of the press, one of the great freedoms for which our forefathers fought and died, a freedom which may easily be the key to the success of our way of life.

It is a tribute to the men like McKee and McCullagh and Ray that they have lived up to the trust placed in them in their use of this great freedom in publishing the “Globe-Democrat.” The tribute has in large measure already been paid by the simple fact of the “Globe-Democrat’s” 100 years of existence.

(Originally published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat 11/9/1952. Author Robert Willier was the senior partner of the St. Louis public relations company Robert A. Willier and Associates.)

As editor, however, Little Mack truly hit his stride. His crusading spirit was an invigorating element in the ‘80s and ‘90s, perhaps unequalled in St. Louis’ history. Why, he asked, was St. Louis so slow in railroad development and service? He began a campaign, sent reporters into the Southwest to show the developments resulting from railroad service; he opened his own railroad department; he editorialized.

As editor, however, Little Mack truly hit his stride. His crusading spirit was an invigorating element in the ‘80s and ‘90s, perhaps unequalled in St. Louis’ history. Why, he asked, was St. Louis so slow in railroad development and service? He began a campaign, sent reporters into the Southwest to show the developments resulting from railroad service; he opened his own railroad department; he editorialized. When it is recalled that the rivalry of these two papers began in 1852, that the “Republic” in its last decade was owned principally by one of St. Louis’ most representative citizens, David R. Francis, and that the “Republic” represented a direct line of journalistic practice to the very beginnings of the city, some idea can be gained of the problem that faced President Ray when the “Republic” was purchased in 1919.

When it is recalled that the rivalry of these two papers began in 1852, that the “Republic” in its last decade was owned principally by one of St. Louis’ most representative citizens, David R. Francis, and that the “Republic” represented a direct line of journalistic practice to the very beginnings of the city, some idea can be gained of the problem that faced President Ray when the “Republic” was purchased in 1919. The “Globe-Democrat,” which had opposed President Wilson as a candidate, surprised its readers by supporting President Wilson’s war policies and his League of Nations, while newspapers all over the country were objecting to his “high-handed” procedure. In other ways the “Globe-Democrat” gained stature with its readers by its honest efforts, as the only morning paper, to produce a highly readable, interesting, entertaining and reliable publication.

The “Globe-Democrat,” which had opposed President Wilson as a candidate, surprised its readers by supporting President Wilson’s war policies and his League of Nations, while newspapers all over the country were objecting to his “high-handed” procedure. In other ways the “Globe-Democrat” gained stature with its readers by its honest efforts, as the only morning paper, to produce a highly readable, interesting, entertaining and reliable publication. Publisher Ray, who was for many years a curator of the University of Missouri, has received many honors but values most his distinction of having been for 29 years a director of the Associated Press.Only four men in the whole history of the AP had served longer as a director, when Ray retired in 1951. During that period he served two terms as first vice president. Another distinction he values is that of having been one of the small handful of St. Louisans who backed Lindbergh in his historic flight.

Publisher Ray, who was for many years a curator of the University of Missouri, has received many honors but values most his distinction of having been for 29 years a director of the Associated Press.Only four men in the whole history of the AP had served longer as a director, when Ray retired in 1951. During that period he served two terms as first vice president. Another distinction he values is that of having been one of the small handful of St. Louisans who backed Lindbergh in his historic flight. Now in its fourth building in a century, the “Globe-Democrat has production facilities which are a far cry from the old Ramage press that did well to produce 200 “Missouri Gazettes” a day. But the intricate machinery and methods of today’s modern newspaper plant are not as impressive to the reader as the single paper he gets each morning – its appearance and content.

Now in its fourth building in a century, the “Globe-Democrat has production facilities which are a far cry from the old Ramage press that did well to produce 200 “Missouri Gazettes” a day. But the intricate machinery and methods of today’s modern newspaper plant are not as impressive to the reader as the single paper he gets each morning – its appearance and content.