Radio Articles

KMOX Janitors Became Radio Stars

When Miriam Blue took off her rubber gloves, put down her janitor’s supplies and began talking into a microphone at KMOX radio in 1975, she was following in the footsteps of a man who did the same thing nearly 40 years earlier.

Sol Williams, like Miss Blue, was an African-American (the term in those days was “Negro”) janitor when KMOX occupied studios in the Mart Building in 1938. Co-workers at the station appreciated Sol’s wit and happy banter as he mopped the floors. His advanced age of 70 didn’t stop him from living life to the fullest and loving it.

A debut on KMOX for Sol Williams came at an unexpected moment, a time when sports announcer France Laux suddenly found himself without an expected guest at the beginning of his nightly sports show. Williams had been working as a janitor at KMOX for 10 years, and Laux’s producer knew the man loved sports and had lots of opinions. Larry Neville ran out into the hallway. “Sol,” he shouted.

Drop that mop and come on in here.”

On the air, Laux was stretching, not knowing what was going on. As he saw Sol being escorted into the studio, he didn’t miss a beat. “…and our guest for the evening is the celebrated sports authority, Sol Williams.” There was no evidence of microphone fright, and management quickly found out how listeners felt. Fan mail came pouring in. Sol Williams became a regular guest on the “Hot Stove League” program.

In the late 1930s, almost everything heard on the radio was scripted, but not Sol. Laux reportedly wanted Williams to be himself, and a script would have hampered that. One of the traits that endeared the janitor to the listeners was his humanness. Sol was known for shifting his allegiance if his favorite teams or players let him down. As he once said on the program, “I picks ’em now. There ain’t nothin’ said about me having to stay on a team if it lets me down.”

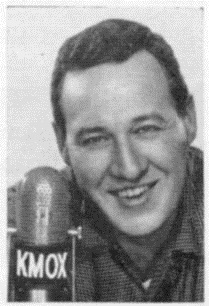

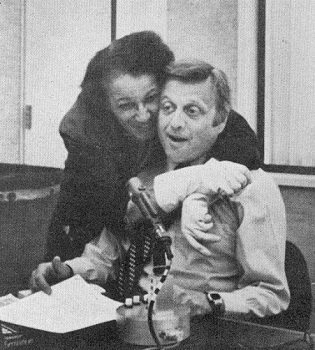

Miriam Blue’s big break came in October of 1975 as she dusted in the KMOX studios while Jack Carney was on the air. At age 61, Miss Blue, as she was known to the staff, was a welcome sight in the studios at 1 Memorial Drive. Known for her constant upbeat approach to life, Miss Blue rode the bus from her home in East St. Louis each day. When asked how she was doing, her consistent answer was a sincere “All is well.”

Miriam Blue’s big break came in October of 1975 as she dusted in the KMOX studios while Jack Carney was on the air. At age 61, Miss Blue, as she was known to the staff, was a welcome sight in the studios at 1 Memorial Drive. Known for her constant upbeat approach to life, Miss Blue rode the bus from her home in East St. Louis each day. When asked how she was doing, her consistent answer was a sincere “All is well.”

As she told it later in her career, Miriam Blue was dusting in Carney’s studio and he began asking her questions. She answered in her usual upbeat manner, not knowing the microphones were on. The reaction from the audience was immediate, just as it had been with Sol Williams, and Carney created a regular slot twice a week at 10:15 on his program for her. She had advice for callers who phoned the program with their problems, and she was later incorporated into Carney’s wildly popular “As the Stomach Turns” skits. She joined the broadcasters’ union, AFTRA, and was paid for her broadcast appearances.

After he got finished on the air each evening, Sol. Williams returned to his cleaning chores around the KMOX studios, and Miss Blue did too, even though a national spotlight began to shine her way. The Associated Press ran a feature article about her broadcast success, which led to an article in People magazine and another on CBS-TV. The game show “To Tell the Truth” flew her to New York to appear as a guest star and she was featured in “The David Susskind Show” on CBS Radio. The New York trip was not only her first time on a plane. It was also her first visit to Lambert Field in St. Louis.

She continued on Carney’s show, as well as in her job as KMOX janitor until she was hospitalized in the early ’80s suffering from a stroke. She passed away in the hospital.

Miriam Blue was once asked by a reporter whether she was making a lot more money in her new status as a KMOX celebrity. Her response was vintage Miriam Blue: “I just couldn’t be happy as the idle rich.”

(Reprinted with permission of the “St. Louis Journalism Review.” Originally published 11/00)