Radio Articles

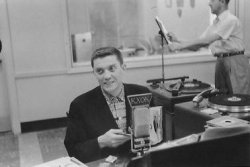

Marvin Mueller at KMOX Scores Success as Kindly Uncle Remus

You can’t ever tell how Marvin Mueller, announcer at KMOX and star of the Uncle Remus Stories, will greet you. He has a perfectly normal voice but he scarcely ever uses it. One time he says hello or comments on the weather with a distinctly English accent or in a broad German – the next time he’s a tottering old Ozarkian or a kindly old Negro of the Southland. It’s no trick at all he says to change rapidly from one person into another by a simple modulation of the voice but whether it is or not – he’s a real artist at it.

Because of this unusual talent, Marvin figures in all of the dramas produced by the KMOX Players and his characterizations are so perfect that the illusion of the actual presence of as many as ten characters at once is created by him.

During the last four or five months since he’s been at KMOX he has “been” Calvin Coolidge, Joseph of Nazareth, Samuel Insull, Abraham Lincoln, George Bungle, Herbert Hoover as well as several hundred original characterizations. He is now heard as the kindly old Uncle Remus, the Optical Service Physician, and has a full-time announcing position.

He was in charge of a banquet at Washington University several years ago and since he was a constant radio listener, he decided to burlesque several of the most notable programs as a means of entertainment. He couldn’t seem to find the right people to help him with the idea and so he did it all himself! Later he decided to try his hand at radio and as an inspiration, he wrote a play titled “The Adventures of Lord Algy” in which he portrayed a ridiculous Englishman seeing the sights of America. He tried out at KWK and the program was such a success that it ran for twenty weeks.

Since that time he has been on WIL where he was featured in the Pirate Club program as Portugee Joe, Professor Pete, The Spider and other colorful figures.

Marvin is a Junior at Washington University – although he has now abandoned the idea of being an English and French professor – and makes excellent grades. Although he has never had any training in elocution, he is a member of Alpha Phi Omega, the national debating fraternity, and has studied public speaking.

For the most part, aside from his real talent, he is a merry sort of chap with deep brown eyes, brunette hair and a ruddy complexion. He is acclaimed as being one of the best authorities on the presentation of classical music programs on the air because of his studies of foreign languages.

His voice comes to you many times each day in plays or regular programs and if you didn’t know his trick, it would seem that he is a different person each time. As Uncle Remus, he glorifies Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox with a humor that is appealing to all ages of listeners and when the script calls for it, this amazing young man adds the singing of Southern songs to his list of accomplishments.

(Originally published in Radio & Entertainment 3/4/1933)