Radio Articles

KMOX – “The Voice of St. Louis” – Engineering History

On Christmas Eve, 1925, KMOX first went on the air from Kirkwood, Missouri, licensed as “The Voice of St. Louis.” A venture spurred by the imagination or 15 prominent businessmen in the community, it was also strongly supported by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. With studios in the Mayfair Hotel, its modified Western Electric 104-A transmitter supplied a husky 5-kilowatt signal to a flat-top antenna system.

Within a very few months, the station developed a personnel problem; its technicians were highly dissatisfied with their weekly wage of $30 for 48 hours. Thus, the first union organization of radiomen took root in St. Louis, at KMOX, when they joined Local Union No. 1, IBEW. Almost coincidentally, the first articles on “Radio” began in the IBEW’s Journal of Electrical Workers and Operators in the April, 1926, issue.

(transmitter remote equipment is at right.)

In September of 1930, a new transmitter went on the air, and from a new location. The 5-kilowatt transmitter was replaced by a 50 kw. rig operating from Baumgartner Road, near the Meramec River, 14 miles south of St. Louis proper.

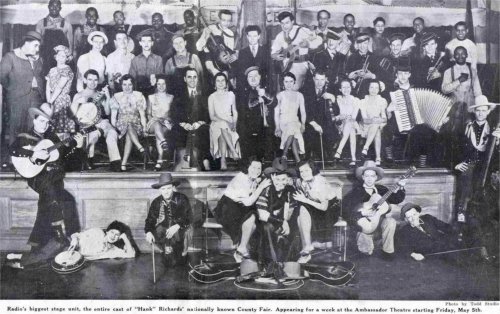

In 1932, the studios were moved to the St. Louis Mart Building, where they remained for many years thereafter. It was generally said, at that time, that the new studios was a far cry from KMOX’s humble beginning, when the first tinkling notes of “Somewhere A Voice Is Calling” announced the first presence of the new station in town. That same year, CBS purchased KMOX. And by the end of the year, the list of CBS owned-and-operated stations had grown to eight: WABC, New York; WBBM, Chicago; WBT, Charlotte; WCCO, Minneapolis; WJSV, Washington; WKRC, Cincinnati; WPG, Atlantic City; and KMOX. With one affiliate in Canada, the relatively new network consisted of 93 stations.

The accumulation of plaques, certificates and similar testimonials of awards for programs, community and public services and the like almost literally cover a large wall in the present studio building on Hampton Avenue. And these are the awards of only the recent years. From its 5,000 watts in the early days, to its present 50 kw on 1120 kc., from its ponderous motor-generator sets of the ‘20s and ‘30s, the 104-A and the 5-C (later used by a station in Macon, Georgia, and until mid-1958), to its present air-cooled Westinghouse HG-1 and the Continental companion auxiliary at Stallings, Illinois – all are just about as far distant from each other as 1925 is from 1963.

KMOX-FM went on the air in February of 1961. Its Collins 830-Z-1A transmitter is licensed for 47 kw. ERP on 103.3 mc. This transmitter is remotely-controlled, as is the AM, from the studio and is located in the KMOX-TV transmitter building in Lemay, Missouri.

In December of 1960, KMOX began the operation of its transmitters by remote control. To date, it may well be the only station in the United States (or perhaps the world) which now employs a greater number of engineers than it had on the payroll prior to the advent of its automation. With heavy emphasis on sports, news and discussion programs, manpower requirements are correspondingly high; both the need and the fulfillment are tributes to the station activity and the far-sighted and astute management of “The Voice of St. Louis.”

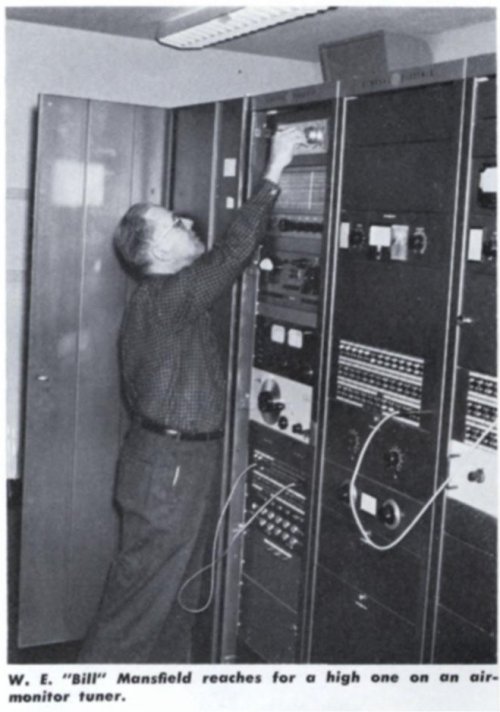

When L.U. 1217 was chartered on December 18, 1940, the engineering staff became charter members of that Local Union. Among the signatures on the actual charter are at least two members still employed at KMOX: W.E. Mansfield (many times a local union officer) and Chalmer H. Stoup. Another member with a long and distinguished record of service with KMOX and his local union is Robert W. Stetson, who has been enjoying retirement for some little time. Brother Stetson was the Financial Secretary of Local Union 4 when he retired on September 1, 1960. All the names on the original charter issued to 1217 were duplicated on the new one when Local Union 4 was chartered on January 1, 1959.

Thus, this month we are happy to salute this “old time” station and the men who have kept and are keeping it on the air. But few stations have such a long and parallel history with the IBEW. Theirs is indeed a proud heritage and a bright future.

(Originally published in Technician-Engineer 4/63).