By Nancy Frazer

Seated at the tiptop of Sportsman’s Park at the side of France Laux, KMOX’s popular announcer, offers both a mental and verbal picture second to none. At that commanding position where the park looks like an artist’s dream, the game should be apparent in even its tiniest details – but it isn’t unless Laux is describing it.

Personally, I am not much of a baseball enthusiast or wasn’t until I heard him talk about the game so familiarly and colorfully. Since seeing the game through his eyes and my own simultaneously, I am convinced that one actually derives as definite a picture of what is taking place through his description while seated comfortably by the radio as if one were actually there.

While thousands of persons in homes and on the street and in automobiles are awaiting his next word, France Laux’s head in bent close to a microphone with his eyes on every player in the game. He catches every movement and the words are on the air before the ball stops and while the actual spectator is wondering what the result will be. I heard what he said and with my eyes glued on the plays I still couldn’t see what was going on until he had already sent the words bounding out through the ether.

The amazing part about it is that he rarely, if ever, makes a mistake. He knows the game thoroughly, having played baseball in all positions and all over the state of Oklahoma. He has played in all the major sports and served as coach and instructor to the extent that he is renowned in the Southwest. He is even popular as an umpire, and that is saying something!

I always fancied when I merely heard of him that he must have lists of names and score cards and all sorts of historical data piled before him which he fumbled through in order to get the information out in time. But he doesn’t! He merely has an ordinary scorecard and a package of cigarettes and a head full of personal and historical information about each of the players. With each play he puts down a system of circles and dashes which mean worlds to him.

They meant so little to me that I prevailed upon him to explain while Ray Schmidt was summing up the events at the end of the innings.

He has worked out a system of recording all his own so that every one of the minute hieroglyphics means a player or a play to him. He is so well versed in the game that he knows what the decisions are and he can tell them as quickly as the play is made. He does however keep a weather eye on Martin Haley, official scorer, who sits over in the press box across the tiptop way. If there is any doubt, the scorer nuts up a finger or lays it down and they understand each other.

Laux tells that happens in an unbiased and simple way leaving out all adjectives, since he feels that if people are interested in listening to the game at all they want only information as to what transpires and not any comments of his own. As simple and as few as the words are, he has the most graphic command of descriptive words that I have ever heard.

I tried listening and looking. Then I tried just looking at the game and then merely listening to him and I found that I enjoyed the game much more with the mental picture and hearing him calmly and accurately verbally parading the plays out over the air.

France Laux started participating in sports via the radio announcer way in a spectacular manner.

When the Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Yankees were playing in the decisive game in the World Series, the sports announcer at KVOO suddenly quit and there was no one to announce. The powers were in a quandary while they realized that there was but one person in Oklahoma who knew the game well enough to describe it. France Laux was fifty miles away and there was but one hour to spare.

They tore down to his town and back again, did an in-motion kidnapping act and had him back in the studio with one minute to spare where he broadcast his first game. Being really catapulted into the announcing field, he made such a success at it that KMOX asked him to come here in 1929 where he was voted recently one of the best announcers in the country. It must be a family trait, however, for he has a brother in New Jersey who is also making a name for himself as an announcer.

Try as he will, though, he can’t keep all the enthusiasm out of his voice and that is toned down by Robert Stetson, engineer for the station, who is continually on the job at the radio booth in the park. He sees to it that the volume is kept down and the voice is modulated even during the most exciting moments.

Anyway, baseball has an ardent devotee. Since becoming a Laux follower I keep mentally reflecting what I have been missing.

(Originally published in Radio and Entertainment 6/11/1932).

Radio station KSHE has made a big step into the lives of St. Louis area teens. KSHE-95 in the past few weeks has changed to “Rock Radio.” Now they have gone a step further and broadcast live every Friday, Saturday and Sunday night from 9 to 10 PM direct from the Castaways, 930 Airport Road in Ferguson, Missouri. />The live broadcasts are emceed by Don O’Day, Big Jack Davis, and St. Louis’ own Johnny B. Goode.

Radio station KSHE has made a big step into the lives of St. Louis area teens. KSHE-95 in the past few weeks has changed to “Rock Radio.” Now they have gone a step further and broadcast live every Friday, Saturday and Sunday night from 9 to 10 PM direct from the Castaways, 930 Airport Road in Ferguson, Missouri. />The live broadcasts are emceed by Don O’Day, Big Jack Davis, and St. Louis’ own Johnny B. Goode. At St. Louis University, she gave the first course in television with academic credit to be given anywhere in this area, plus the first course in radio feature programming to be given anywhere. This radio educational first went out on the national news wires.

At St. Louis University, she gave the first course in television with academic credit to be given anywhere in this area, plus the first course in radio feature programming to be given anywhere. This radio educational first went out on the national news wires. Bob Harms who takes the part of “Tommy” and writes the script for that nightly KMOX feature program “Tommy Talks” gets his inspiration and ideas from many sources. Bob has lunch with a group of office boys and messengers two or three times a week so that he can absorb their ideas and views and pick up their slang expressions. In this manner Harms is able to give a true picture of the thoughts and actions of the average office boy.

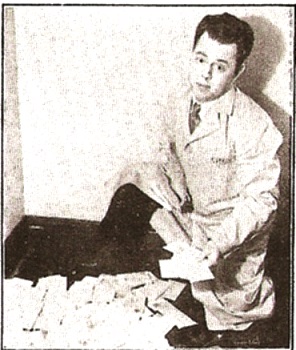

Bob Harms who takes the part of “Tommy” and writes the script for that nightly KMOX feature program “Tommy Talks” gets his inspiration and ideas from many sources. Bob has lunch with a group of office boys and messengers two or three times a week so that he can absorb their ideas and views and pick up their slang expressions. In this manner Harms is able to give a true picture of the thoughts and actions of the average office boy.