Radio Articles

Castani Wouldn’t Give Up

It was just like those stories you hear the old timers tell: He was a 15-year-old kid who was so fascinated with the radio business that he just hung around the radio station until someone decided to hire him. His name – Dick Castanie.

When Dick was 15 in the late 1950s, he started spending all his free time at the KCFM studios in the Boatmen’s Bank Building downtown. The station had no openings for announcers, but Chief Engineer Ed Goodberlet recommended Dick be hired on a part-time basis to do some engineering work like meter reading.

“I got paid $19 a week for about 35 hours,” he says.

The station’s format consisted of instrumental music tapes. The “studio” from which the broadcasts originated was a room at the top of the building next to the elevator shaft, which made it impossible to talk on the radio when the elevator motors started up.

Castanie says that was no problem. Back then the KCFM broadcasts were based on music, not personality. When listeners heard a voice, it was seldom, if ever, live. The drop-ins were recorded at KCFM’s other building at 532 DeBaliviere – where station owner Harry Eidelman owned and operated a hi-fi shop – and brought downtown to be broadcast. All the music was on huge reels of recording tape which were played on the big machines in that small room at the top of Boatmen’s Bank. Castanie says there was an emergency microphone there to be used should the need arise.

Eidelman had bought the KCFM frequency from KXOK for $1 after KXOK-FM had shut down. In an effort to keep breathing life into KXOK-FM, the station’s owner, the St. Louis Star-Times, had tried something called “transit radio.” The city’s streetcar and bus system had been outfitted with FM receivers tuned to the station’s frequency. But lawsuits shut down transit radio in other cities, and in 1954, Harry Eidelman became the proud owner of the frequency. KMOX gave Eidelman a used Western Electric control board from its old Mart Building studios.

“I remember Harry bought all the radio receivers used in the streetcars,” says Castanie. “We converted them for use in automobiles and sold them over the air for $19.95 apiece.”

A couple years later, Castanie got a chance to jump stations when a friend let him sit in and watch a show. While Dick Kent was on the air on KWK, the 17-year-old Castanie sat in an adjacent room next to the turntable operator behind the glass. These operators were leftovers from the days when radio stations had employed live musicians. Their union, the American Federation of Musicians, negotiated a deal with the station that would allow members to continue employment as “platter spinners.” Castanie was hired at KWK in 1959 as vacation relief for the turntable people, but he had to join the musicians’ union. His dad loaned him the dues, and Dick was soon elevated to a full-time slot.

“I worked with Buddy Moreno and King Richard, and for a short time with Gil Newsome before he went to KSD. Gene Davis was the program director, and I worked with him when he was the midday announcer in 1961,” says Castanie.

That union situation hit an interesting juncture while he was working at KWK. Radio stations were limiting their playlists, so they dubbed most of their popular songs onto tape cartridges. This meant the turntable operators were no longer playing records, and they weren’t supposed to handle the tapes. The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers argued its members should be playing the carts since they were the audio engineers, and the announcers’ union, AFTRA, argued its members should be playing the carts since the little plastic contraptions were part of program content. The entire argument centered on who would push the button to start the tape cartridge.

Castanie has other vivid memories of his work at KWK: “I was there during the ‘treasure hunt’ fiasco, and we had to go to work through the back of the building because the crowd up front was very upset about being scammed.” KWK was later found guilty of hiding the “treasure” in Tower Grove Park the day before it was found by a listener even though clues to its whereabouts had been broadcast for several days. The Federal Communications Commission eventually found the station guilty of conducting a fraudulent contest and revoked KWK’s license to broadcast, shutting down its operation.

When Ed Ceries signed on with a new FM station in St. Louis in 1961, Castanie went to work for him. The station, known as KSHE, featured female announcers playing classical music and was located in the basement of Ceries’ home in Crestwood. Castanie says his work with the new station didn’t last long: “I was let go because they couldn’t afford to pay me.”

Looking back on his experience over the years gives Castanie a different perspective, especially when it comes to the real reason he was hired at his KCFM job. “Years later my uncle, who managed the building, said that Harry [Eidelman] hired me hoping that if he couldn’t pay the rent there my uncle wouldn’t evict him.”

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 11/2001).

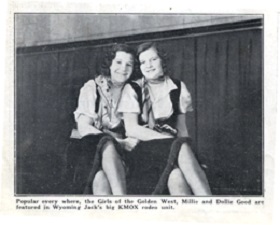

While Dollie, the youngest, was still in school she decided that she wanted to play and sing more than anything else. Her mother told her that she would either have to stop school or stop spending so much time in learning to play a guitar. So Dollie, intent on her purpose, stopped school.

While Dollie, the youngest, was still in school she decided that she wanted to play and sing more than anything else. Her mother told her that she would either have to stop school or stop spending so much time in learning to play a guitar. So Dollie, intent on her purpose, stopped school.