WIL Artists Enjoy Broadcasting in New, Well-Arranged Studio in Star Building But Miss Applause

To the thousands of listeners-in who, last night and Saturday, heard the two opening programs of station WIL, operated by the St. Louis Star and the Benson Company, the inside story of broadcasting should prove interesting.

While the radio fan is glancing at his clock, as the hands near 10 p.m., all is activity at the studio in The Star Building, a pretty gray room with softened walls and muting draperies. Within it voices sound echoless. There are stenciled decorations on the walls, a new grand piano in the center, overstuffed lounges, and on the wall over the microphone a gilded horseshoe.

Bud Fox, the studio pianist, throws down his cigarette and enters the room, glancing at the red light on the wall with its warning that absolute silence must be maintained.

Billy Knight, the Little Old Professor, flits from studio to reception room, where the evening’s entertainers leave their coats and clear their throats. One of the earlier arrivals asks that the horseshoe, sent by a fair admirer and which hangs on the wall for luck be turned prongs up according to tradition, and Billy fixes that, with many other things.

Operator’s Room

Two stories higher sits “Dink” Garrison, the operator, in a little room reminiscent of the radio operator’s quarters aboard ship. Around him are switchboards, receiving sets, batteries and telephones. A direct line connected him with the studio below, and with a telephone circuit operator stationed at the Arcadia Ballroom, where two orchestras are already playing.

It is ten, lacking a minute. The Professor has finished a telephone conversation with Dink. Bud Fox has smoothed out his long black hair, and Miss Toots Thurman, a good looking girl with auburn hair and a dress the color of burnt ochre, is standing before the microphone, the bronze ear of all those listeners out in the cold distant world.

“Now everybody quiet,” says the Professor. The piano starts, followed a few seconds later by the words of “Roses of Picardy.” Up in the operator’s room, the needles on the dials are swinging, measuring the voice modulations, and sending them on their far flung circuit.

Performers “Doll Up”

In the studio, the most striking thing is the interest of the performers in their appearance. No shirt sleeves here, but pearl necklaces, satin slippers, careful marcels. Each singer has his or her set habit. One digs the heel of her shoe into the thick carpet, another fingers his watch fob, while Bonita Frede, a child blues singer, is assured by her mother that it will be quite all right for her to bend her knee in time to the music and roll her eyes, too, if she wants to.

The microphone provides something to sing to, as it stands unemotionally on its glass stand, but there is nothing in particular to look at and the glance of the singers roves over the wall before them.

But even before the program began, the two telephones in the reception room started to ring, to continue during the whole evening. Some called to say “It’s coming in fine,” and turned away from the phone so that the voice of their loud speaker returned over the telephone wire to the place whence it started on the ether. There were telegrams, too, and requests for favorite numbers.

The majority called to comment on the remarkable clarity with which station WIL is heard on receiving sets. This clarity, according to WIL fans, is in marked contrast to the indistinct reception of some other stations on which they have been accustomed to tune in.

One thing is lacking, though, when midnight comes and signing off time. Half the fun in good singing or acting is the applause. All radio singers get is the silent approbation of the half a dozen persons in the studio, who smile and clap in pantomime at an extra good note.

(Originally published in the St. Louis Star Feb. 3, 1925.)

It’s seldom that an amateur who turns to the professional ranks succeeds on the first attempt—unless the amateur is as gifted as Mary Lee Taylor.

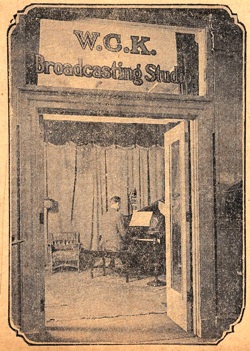

It’s seldom that an amateur who turns to the professional ranks succeeds on the first attempt—unless the amateur is as gifted as Mary Lee Taylor. The radio station, WCK, Stix Baer & Fuller of St. Louis, is ever a popular one in Divernon (Illinois) and last Tuesday through the courtesy of Alva B. Jefferis, the editor had the privilege of visiting Station WCK while broadcasting was in progress at the noon hour, and meeting Miss Hatfield, the announcer, whose calm pleasant tones are identified by thousands of invisible listeners as “WCK.”

The radio station, WCK, Stix Baer & Fuller of St. Louis, is ever a popular one in Divernon (Illinois) and last Tuesday through the courtesy of Alva B. Jefferis, the editor had the privilege of visiting Station WCK while broadcasting was in progress at the noon hour, and meeting Miss Hatfield, the announcer, whose calm pleasant tones are identified by thousands of invisible listeners as “WCK.”

“This is Station KSD, the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch. We are about to present our first musical program for your enjoyment.”

“This is Station KSD, the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch. We are about to present our first musical program for your enjoyment.”