The best part of being an avid radio listener in the 50s and 60s was the accessibility of people on your favorite stations. Many listeners felt as though they “knew” the folks they heard on the radio. A few made the effort to get to know a lot of radio people at a lot of stations.

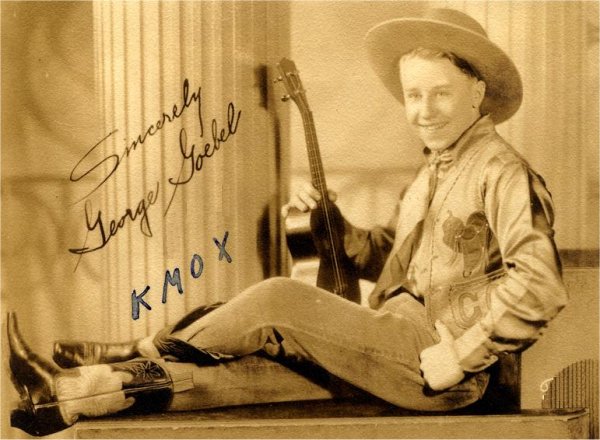

Take Jerry Mitchell, for example. In 1947, at the ripe old age of 10, Jerry would hike from his home at 18th and Russell northward to the Mart Building, which was then the home of KMOX. “I would go up and sometimes they would take me back into the studios. There was a musical show then featuring Russ Brown and the KMOX Orchestra, and they’d let me watch the broadcast.”

Mitchell continued his radio visits, even through his adult life when he worked delivering mail for the Post Office. “In most of the stations the people were friendly. At KATZ in the Arcade Building they were particularly friendly. I am white and their on-air staff was all black, but that didn’t matter. Gracy was very gracious to me, and Dave Dixon, of course. I knew Jerome Dixon from the Post Office, and he did some on-air work. Out at the old KXLW in Brentwood I met E. Rodney Jones. I’d go into the studios and talk to all those guys.

“I remember Spider Burks when KXLW was in Clayton. It was so novel in those days to have a black man on the air, especially on an otherwise all-white station. It was Spider Burk and his ‘House of Joy’ program. Later on he had a coffee house at Gaslight Square. There was a place called ‘The Dark Side’ and Spider had a coffee house in back of that called ‘The Other Side.’ They had a great jazz combo in there.”

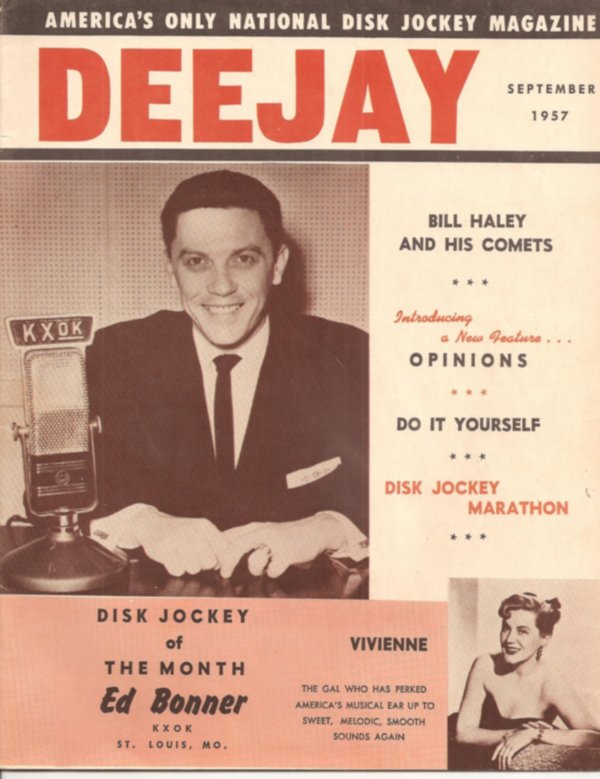

In the late 1950s, there was a classic battle among this city’s popular music stations. KXOK suddenly faced a challenge from an upstart at the right end of the AM dial. “WIL came on with Color Radio and knocked them out of the box. They had such a stable of jocks: Jack Carney, Bob Osborne, Gary Owens, Bob Hardy with ‘Action Central News,’ Ron Lundy, Dan Ingram, Dick Clayton – what a droll, funny guy he was.”

It wasn’ t just a matter of being able to walk into the studios to talk with the jocks. “WIL was in the old Coronado Hotel, and some of the secretaries there really thought they were gatekeepers, and I guess with their teenage audience they had to be. The studios were in the basement, and you entered off a patio just to the west of the hotel entrance. Things were sort of cramped.”

Meanwhile, at KXOK, “Radio Park was a dandy facility. I think they bought it in anticipation of getting a TV license. North Kingshighway was a good neighborhood. They had a Parkmoor and the station facilities were just great.

“I remember KWK from the forties. Ed Wilson was always one of my favorites, and Gil Newsome, or course. Ed was probably one of the better salesmen in the history of radio. Any commercial he ever read sounded like a personal endorsement. It wasn’t ‘Go to Central Hardware.’ It was ‘Mom and I went to Central Hardware last night.’”

KSD moved out of the Post-Dispatch Building and into new studios at 1111 Olive. “I remember they always sounded so dignified. They had some guys with some great pipes: Walt Williams, Bob Ingham, Howard DeMere. Later on they had the guy I considered to have the best voice in St. Louis radio history, Harry Gunther. I got to sit in with him a few times. Bill Calder would rag Harry on the air because he preceded him. Harry was doing a jock show from like 7 to midnight, and Calder would spend about half of his time using old Jack Carney material and giving Harry a hard time because of his great pipes.”

When WEW was sold to Bruce Barrington by St. Louis University the format was changed. “They played country music for awhile. They were in the Landreth Building down on North Fourth Street.

“KMOX also moved around. They moved out of the Mart Building, but their new building wasn’t ready, so they went to Ninth and Sidney. I remember seeing Harry Caray there. He was a dresser, the epitome of sartorial splendor. They had a very nice facility in what was the previous office of Bank Building Corporation. I remember delivering mail to the new studios on Hampton. Jack Buck would always speak to me. You know, he never meets a stranger. I always thought KMOX was the greatest station I had ever heard. I remember they used to do a quiz show on Sunday nights called ‘Quiz of Two Cities.’ They would have teams from each town, and Jack Sexton, who later became Jack Sterling, and Al Bland were the quiz masters.”

Even for a little kid radio could be fun. “I remember going over to WTMV when I was real little and talking to Santa Claus. It was in the Broadview Hotel in East St. Louis, and I never actually got to see Santa. His voice came through a speaker. That way they didn’t have to spring for a costume.”

Ask Jerry Mitchell who stood out more than anyone else in all his years of radio listening and the answer comes quickly: “Jack Carney. When Carney left WIL and went to New York. I missed him – I missed him like one of the family. And it seemed like he was gone for so long, but it was only about six years before Mr. Hyland brought him back to town. My brother used to listen to him in San Francisco, and he remembered him as a great salesman on the radio.”

Today the personal aspects, as well as much of the personality, are gone from radio. But those of us who lived through the earlier times remember them with fondness, even if we never did get to visit the studios.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 12/1999)