Radio Articles

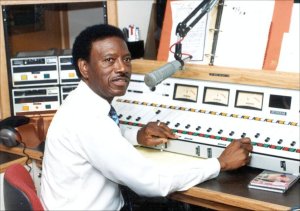

Columbus Gregory – Gospel Pioneer

When Columbus Gregory first walked through the doors of KATZ in St. Louis, his only goal was to sing on the air. In the half-century that followed, he did a lot more.

Gregory had been raised in the South and had been assigned to Korea for his military service. While he was there he heard a friend talking about this Negro disc jockey in St. Louis who had become a major celebrity. When he rejoined civilian life, Gregory headed toward St. Louis to hear the man everyone called “Spider.”

Spider Burks was, indeed, a celebrity, spinning jazz records on the radio and making personal appearances at local clubs almost every night of the week. Columbus Gregory got a job with the railroad, and, in his spare time, began singing gospel with a local quartet called the Victory Airs. In conversations with other gospel singers, he became convinced that their groups would draw better crowds to their performances if listeners could hear them on the radio.

Gregory organized eight of the groups and arranged to buy a half-hour time block on KATZ every Sunday morning. Two groups would sing each week and every group would put $5.00 in the pot to cover the $40 weekly charge. The process worked, but, one-by-one, the groups dropped out, leaving Columbus Gregory with the contract to purchase the time.

The railroad job was not working out, but Gregory’s skills at packaging radio time and at entertaining were developing. In 1959 he got word that the station was looking for a man who can handle engineering work for disc jockey remotes and promotions for the station and he jumped at the chance. Soon he found himself in local grocery stores during the day, promoting products advertised on KATZ, followed by late night work at local clubs supporting the DJs. It was a seven-day-a-week job.

“I did that for three years, “says Gregory. “I was Dave Dixon’s engineer at night. George Logan did some Saturday afternoon things and I was called in to do all his remotes. When Dave Dixon passed, his brother Jerome took over and I was his engineer. I was Spider Burks’ engineer over at the Blue Note Club. In 1963 I decided to try to become an announcer.”

It was a logical goal because the life of an engineer wasn’t particularly glamorous. “Back then we were playing 45s and lps and I had a remote mixer. I’d always sit in the store room of the club and they had a microphone in the front for the disc jockey. I had to work off their cues. Dave Dixon’s vocal cue was ‘Night Beat Down Rhythm Street.’ When I heard the word ‘street’ I let the record go.”

Things were different in those days, according to Columbus Gregory. “The radio announcers today aren’t nearly as popular as they were back then. In the ‘50s and ‘60s in the Black community, if a person wore a military uniform, they were looked up to as really being somebody special. Radio announcers then were held in the same high regard.

“Today’s disc jockeys are searching for popularity. Back then, they weren’t searching for it. They were popular just being themselves.”

Gregory has worked with many disc jockeys over the years, but his most fond memories are of Dave Dixon. “Dave was a real guy. He wasn’t phony. If you weren’t doing your job, he’d tell you, and that’s the way to help a person. You don’t help a person by telling him ‘Oh yeah. You’re doing great. You’re great.’ “Dave would take time to tell me how to do things better, and that made me a better engineer. He was one of the nicest guys I worked with.”

In 1963, Columbus Gregory went to KXLW as a gospel announcer. GM Richard Miller doubled his salary to bring him over. Before he knew it, Gregory was holding down a six-hour shift Monday through Friday mornings. “I always included the audience in the program. I’d even take requests from callers and let the callers talk on the air. Richard Miller loved that.”

KXLW played secular music as well as gospel, and Columbus Gregory says Miller really had a knack for getting the best talent. Guys like George Logan, Jimmy Bishop and Steve Byrd were on KXLW, but one day, they were all gone. A forward thinking programmer by the name of Bernie Hayes had hired all of them away to go to work on KWK.

In response, KXLW went gospel full time, and Gregory was appointed program director. “I brought in Leonard Morris, Louis Bates and Hosea Gales. That was back in 1968. I was with Richard from 1963 to 1979, even though I began working on WGNU-FM full-time in 1976. I’d do an hour or so at sign-on for Richard before going to the WGNU studio in Granite City.

“WGNU-FM had a lot of gospel music that I had overlooked. It had string sections and bands and I said ‘Wow!’ I was on from 10 – 2 Monday through Friday, and I had people calling the station to buy advertising time.”

He later worked for over 25 years as a gospel music on disc jockey on KIRL.

Columbus Gregory’s quest to minister through gospel music on the radio kept him on the air well past the standard retirement age of 65, and he prided himself in the fact that people who listened could never tell how old he was.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 6/05)