Radio Articles

Brewery Sponsors Unique Radio Program

By Harry F. Wild

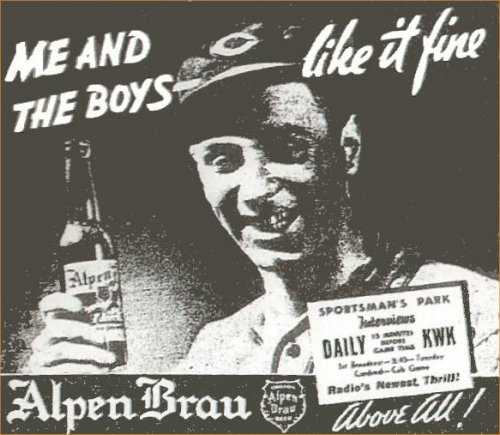

To the average American there are two things which make hot weather bearable – namely baseball and beer, a combination as truly American as any tradition handed down since ‘76. And for that reason the radio program of the Columbia Brewing Company must be considered a strategic bit of sales.

It is the baseball motif that makes the Columbia program an unusual one. The program, known as “The Man-in-the-Stands Broadcast” was heard for the first time on April 14, when the St. Louis Cardinals and the Chicago Cubs opened the 1936 National League Baseball season at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. The program, scheduled daily, is broadcast direct from Sportsman’s Park. It consists of impromptu interviews with baseball fans in the stands, prior to the game, and makes for a chatty, interesting type of broadcast. Radio Station KWK, National Broadcasting Company outlet in St. Louis, is handling the broadcast.

“Alpen Brau,” the Columbia Brewing Company’s brand of bottled beer, is featured on the commercial side of the broadcast.

The program goes on the air daily at 2:45 o’clock – fifteen minutes before the game begins. The fact that KWK is broadcasting all weekday games of the two St. Louis major league teams assures the “Man-in-the-Stands Broadcast” an unusually good ‘spot.” For already the rabid baseball fans – and all St. Louisans take their baseball seriously – are discovering that the “Man-in-the-Stands” is the kind of program that makes those last few minutes before game time slip by like magic.

There was a time, too, when anything built around the baseball motif was generally considered for “men only.” That isn’t the case today, for women have become devout followers of baseball, thanks to radio broadcasting, “ladies’ days,” and other promotional efforts.

For that reason the Columbia Brewing Company’s radio program is the type that arouses the interest of the feminine radio audience. For that reason the concern can get over its sales message to the housewife.

But, by and large, the success of radio advertising depends almost entirely upon the program backing up the advertising. That is why the advertising of the Columbia Brewing Company is getting results. By utilizing the baseball motif – a sport which appeals to everyone – the company has produced a type of radio program that has the same wide appeal.

(Originally published in Brewers’ Journal May 1936).