By Catherine Snodgrass

“Radio announcers!” What an interesting title. When one hears the suave or peppy voice of a radio announcer, he oft-times wonders just what the owner of the voice is like; so I’m going to give you a little personal insight into the life of WIL’s announcers.

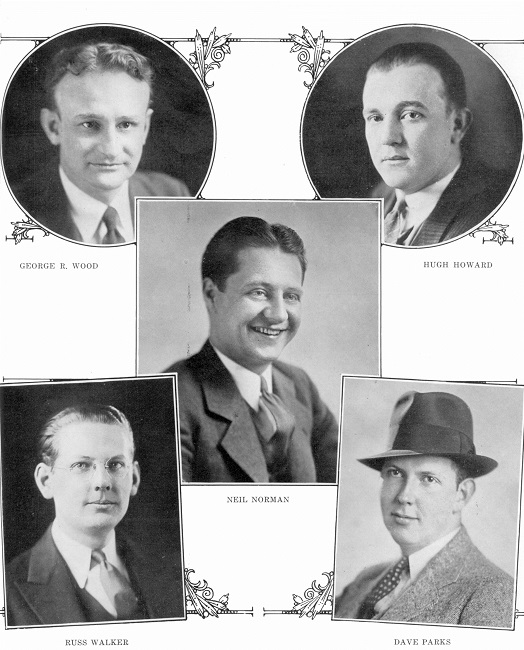

Let us begin with Neil Norman, Program Director. Neil’s full name is Neil Norman Trousdale. He is of medium height, has brown hair, which is inclined to wave, and an every ready smile.

He is the third generation in his family to follow the stage. He not only played leading parts but has enjoyed the privilege of directing his own shows. His mother is still an actress of note on Broadway. He is a talented musician and while conducting an orchestra and acting as Master of Ceremonies in a theatre in Sioux City, Iowa, in 1924, he was offered a job as an announcer, but he turned it down, considering radio a big toy. Four years later he was convinced of the possibilities of radio for entertainment and expressive purposes and accepted a position as announcer at Billings, Montana. He was connected with KSL in Salt Lake City and WMT in Waterloo, Iowa, before coming to WIL.

Neil is very versatile and has a keen sense of fitting the right program at the right hour. He also has a pleasing personality which enables him to handle auditions with the greatest of ease. Neil’s favorite diversion is golf. His chief reason for not playing the game is, “I can’t find a punk enough player to make the game interesting.”

Neil is very versatile and has a keen sense of fitting the right program at the right hour. He also has a pleasing personality which enables him to handle auditions with the greatest of ease. Neil’s favorite diversion is golf. His chief reason for not playing the game is, “I can’t find a punk enough player to make the game interesting.”

When I asked George Wood about himself, his answer was, “Oh, I am just WIL’s oldest announcer.” Don’t be misled by that statement. George wasn’t referring to his age. He was referring to his length of service at the station. He was with WIL for three years serving as announcer and program director. Then he was seized with a case of wanderlust and nothing would do buy George must see the radio world in other cities, so he left the staff and traveled through Missouri, Illinois, Arkansas, Kansas and Washington, D.C., inspecting radio stations and doing announcing. He returned to WIL last Fall as announcer.

Before being seized by the radio bug, George saw service in France in the World War. He entered the business field as a newspaper reporter, then editor. Later ambition made him a newspaper owner. This meant he sold advertising, was reporter, printer, distributor and owner all in one – some job.

George came into the radio fold as a singer on KGFJ, then went to KOIL as publicity director and just dropped in on the announcing game. He continued with KOIL until he came to St Louis and finally to WIL.

And now for WIL’s Junior Announcers:

Some three years ago a tall blond boy answering to the name of Russ Walker ambled into the studios of KMOX to listen to a friend broadcast. After the program, in which the friend had acted as announcer for the “Lions’ Club of St. Louis” the visitor exclaimed “Gee, you sounded great. I’d be scared to death if I had to do that!” Subsequent events proved that he was right. He did announce the program the following day and was quite properly scared. It all happened when his friend, Homer Combs, had to drop his announcing duties to accept a teaching position at a county high school and named Russ as his substitute. Russ was allowed to finish the series of broadcasts for the Lions’ Club, and following this was offered a place on the staff at KMOX.

After four months as a staff announcer he heard the call of the great open spaces of Illinois and went to Springfield, Illinois, as Chief Announcer of WCBS. From there he jumped to the windy city as announcer and jack of all studio trades at WBBM, a Columbia outlet, Chicago. He has had the honor of announcing both Paul Whiteman and Ben Bernie’s Orchestra on the network.

Russ returned to St. Louis and was associated with WIL in 1931 but decided to take a whirl at selling for a while, and acted as district representative for a manufacturing concern. He’s now back in the fold at WIL.

His diversion from the hectic atmosphere of radio is tennis. He and his partner won the doubles championship at one of the CMTC Camps once upon a time! Enjoys all sports and is an admirer of C. C. Petersen, the billiard wizard, but would rather be caught watching the ball pass down the sideline than anything else. Russ grinned when asked his age and tossed his hair back from his forehead with “Oh I’m twenty five but no fair asking any more questions and the size of my shoes is an absolute secret.” Well, that’s all the info I could get from him, but I do know he’s a six foot one and one-half athlete and not married.

Hugh Howard, the latest addition to the WIL staff of announcers is still in his early twenties. Until coming to the station, Howard was a radio columnist for RAE and his pert criticisms caused considerable comment.

The Wolverine State, Michigan, was the scene of his first radio work. The show-world also attracted him while a resident of that state and he found himself for some time a unit manager for the Butterfield Michigan Theatres, Inc., who operate over 100 theatres in that district. Hugh was born in East St. Louis, Illinois, March 13, 19—but that would be telling.

Baseball and canoeing monopolize his sport enthusiasm and his pet passions are program production and Walter Winchelling.

Howard took an active part in the Radio Players’ Guild of this city and portrayed important roles in many of the Guild’s productions. He is an earnest worker with a good voice and really enjoys his hours of broadcasting.

Now for that announcer extraordinary – Dave Parks, who is known to the radio audience as “The Old Reporter.” His real name is David Pasternak. It used to be that only girls changed their names but now radio announcers have that privilege. Dave was born in St. Louis slightly less than twenty-five years ago, and attended public schools of this city and Washington University. After leaving school and up to the time he joined the staff of WIL last August, Dave was engaged in the advertising business. He entered radio as the first “Inquiring Reporter” on any radio station.

For the past four months he has been handling sports at WIL, and in doing so has returned to a “first love” for sports writing. He thoroughly enjoys every sport and enjoys discussing the merits of the players.

While in the advertising business, Dave used his evenings in writing and producing musical shows for private organizations.. He did considerable writing of lyrics for Milton Slosser at the Ambassador. He possesses a keen sense of rhythm and a fondness for good music. He was a member of a college dance band for five years and also worked one season in Vaudeville. Dave says his chief enthusiasms are writing lyrics and eating at night. The last “sport” seems to be the universal failing of all. When asked about girls Dave blushed to the roots of his very curly hair and said, “Oh, I am a confirmed bachelor,” and he really doesn’t like girls unless they are blondes, redheads or brunettes.

His favorite sport to play or watch is basketball. His chief ambition in life is to write something that other people will enjoy reading. Here’s trusting that someday we’ll see “Dave Parks’” name on a popular seller.

Now that I have given you the so-called lowdown on WIL’s announcers, I am sure you will agree with me that they are human, likeable young men with high ideals, enjoying their work and endeavoring to furnish high class entertainment and joy to their listening audience.

(Originally published in Radio and Entertainment 7/8/1933).

About three years ago, Roy Queen, the Lone Singer, decided that he wasn’t quite satisfied with life in Ironton, Missouri and wanted things to happen. He took a couple of bicycle tires and traded them for a 22 rifle but found that wasn’t quite what he wanted.

About three years ago, Roy Queen, the Lone Singer, decided that he wasn’t quite satisfied with life in Ironton, Missouri and wanted things to happen. He took a couple of bicycle tires and traded them for a 22 rifle but found that wasn’t quite what he wanted. Neil is very versatile and has a keen sense of fitting the right program at the right hour. He also has a pleasing personality which enables him to handle auditions with the greatest of ease. Neil’s favorite diversion is golf. His chief reason for not playing the game is, “I can’t find a punk enough player to make the game interesting.”

Neil is very versatile and has a keen sense of fitting the right program at the right hour. He also has a pleasing personality which enables him to handle auditions with the greatest of ease. Neil’s favorite diversion is golf. His chief reason for not playing the game is, “I can’t find a punk enough player to make the game interesting.”