Radio Articles

Three Comics From Topeka Captivate St. Louis Hearts

(By Nancy Frazer)

Getting Henry, Zeb and Otto all rounded-up for an interview requires so much effort that I was exhausted when I finally got them cornered. Gasping for breath, I, by degrees, managed to get this much information out of them.

They are quite as aimless off the air and the stage as they are on – even after I got them all together, they sat on the edges of their chairs and wanted to know after each question whether or not that was all and they could go. How they ever all get into a studio at once remains a miracle but we have their daily programs over KMOX as positive evidence of their one-purposeness when it comes to music.

They are quite as aimless off the air and the stage as they are on – even after I got them all together, they sat on the edges of their chairs and wanted to know after each question whether or not that was all and they could go. How they ever all get into a studio at once remains a miracle but we have their daily programs over KMOX as positive evidence of their one-purposeness when it comes to music.

They were all born in Topeka, Kansas, and all came to radio by devious routes. Being all born in one place is about the only unified thing about them except their programs and so we’ll have to take them singly.

Henry – the first in point of name of the trio – is Merle Hausch and plays the guitar as well as sings with Zeb. Some years ago, a paper hanger in Topeka had a dream of being on the radio in an act named Henry and Hiram. He had never been on the air in his life but the dream was so impelling that he took the name Henry and started out to find himself a partner. Two weeks later, he was on the stage in Topeka doing the act of which he had dreamed (This is a true story. All three of them swear to it).

He took guitar lessons from the time he was twelve years old and the first tune he learned was “Gates Ajar.” So it was with guitar playing that he essayed to make his radio fame – and he has. He went from Topeka triumphs to Chicago and then to the Dixie Columbia Chain. When his act with Hiram was broken up, he found Zeb and then they set for Otto. They had never met before – although they grew up in the same town!

Then there’s Zeb, whose real name is Rene Hartley. He always smokes a big, black “seegar” and notoriously never talks on the air. He is reticent about himself but this we managed to elicit from him.

He took his first violin lessons from a Negro who was in jail – no Zeb wasn’t in jail but the Negro was and he was the best violinist in Topeka. So every day the little lad trudged down to the jail to learn to “fiddle.” Since that time he studied two years with Bissing in Chicago.

He has had two orchestras all his own in Topeka and Kansas City where he violined and led and has composed several song hits. He does all of the arranging for the three as he did for his orchestra. He is tall and slender and has gloriously wavy hair. He is not sure where he got the name Zeb except that youngsters always called him that.

Making personal appearances lately, he has gone back to stage work from whence he came but he likes radio work best of all. “More interesting,” he says, with Calvin Coolidge brevity.

Last, but in no way least, is jovial Otto who was christened Ted Morse. He played a bugle much to the delight of all his neighbors and had a band all his own when he was a youngster. His family bought him and trumpet and a trumpeter he has been ever since. He started in stage work at a very early age and appeared here with the “Six Brown Brothers.”

He was the leader of the 139th Infantry Band in France and graduated from the American Band Leaders’ School in Chaumont, France. He sings second tenor with Henry when their voices come over the air. He is jovial and as much like the title “Otto” as anyone could possibly be. The others gave him that name when he joined them in Chicago.

Otto’s favorite tune to sing is “Ach die Lieber Augustine” and by some amazing manner he has managed to grow one hair on his head that has attained the length of four inches!

They have a collection of more than 700 songs that they sing including ballads, hymns and hillbilly music and they nearly always play with their music perched in front of them. The only tune that they could all agree on as being their favorite was the “Naughty Waltz.”

Zeb supplies the arrangements. Henry has amassed the words for their songs and Otto is the droll wit. They all contribute real musical training and experience to make them the popular trio that they are.

There they are – at least those are the last words that I managed to get as they rushed off in three directions. All born in Topeka – got together to make radio fame in Chicago and came to KMOX where they have made it.

And that’s Henry, Zeb and Otto when they whale into their rollicking melodies with “Let ‘er go, Zeb – Let ‘er go.”

(Originally published in Radio and Entertainment 10/29/1932).

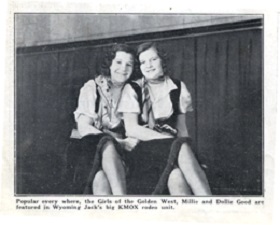

While Dollie, the youngest, was still in school she decided that she wanted to play and sing more than anything else. Her mother told her that she would either have to stop school or stop spending so much time in learning to play a guitar. So Dollie, intent on her purpose, stopped school.

While Dollie, the youngest, was still in school she decided that she wanted to play and sing more than anything else. Her mother told her that she would either have to stop school or stop spending so much time in learning to play a guitar. So Dollie, intent on her purpose, stopped school.