Radio Articles

When Chief Engineers Still Climbed the Towers

Ed Bench came back to St. Louis in 1948 after his military service and his timing was perfect. His strong engineering background made him a prime candidate for the job of chief engineer at KSTL. James Grove, the president of Grove Laboratories in St. Louis announced his new station in February of that year, and he hired Bench to build it. Studios would be in the American Hotel, but there was a problem at the outset with the union.

In Bench’s words, “We were in the broadcast part of it and they were in the wiring part of it and they said ‘We have to wire all this.’ So they came in and created such a jumbled mess. They had no idea what was needed in a broadcast station. So we let them finish the job and when they got done we disassembled it all and put it back together the correct way.”

KSTL’s studios consisted of an announcer’s booth and a large studio with a piano and room for small bands. Engineers sat in a separate control room and spun the records, but that wasn’t their only duty. “Back in those days you had to have an engineer with an F.C.C. first class license on duty constantly at the transmitter, and they had to log the readings from the transmitter every half hour.”

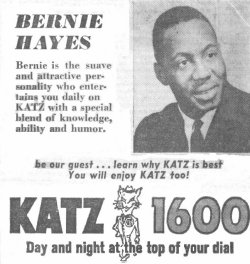

Bench stayed with KSTL until 1955, jumped to television for four years and then built KATZ, which was put on the air by St. Louis Broadcasting Company, owned by Bernice Schwartz in Chicago. “When we went on the air we were only a one kilowatt daytime operation. After we put in a directional antenna, we went to a day/night broadcast and increased the power to 10,000 watts.

“One day I got a call from my good friend Harry Eidelman. He asked me to come out and visit because he wanted to show me something. He had a blueprint and a little tin box, and he told me it was Multiplex, which he said allowed him to broadcast a second signal on an FM frequency. I went down to KATZ and resigned and went to work for Harry.”

The problem was that FM radio just wasn’t cutting it, and Eidelman’s little box, in Ed Bench’s eyes, could save the industry. The station could run its regular broadcast and put something else more profitable on the sideband frequency, like Muzak, which is what Eidelman ended up doing. The additional Muzak income helped the station survive.

Bench had helped his friend Eidelman apply for the KCFM frequency several years earlier. “When I went to work with him I talked him into moving the tower from Boatmen’s Bank downtown to the studio building at 532 DeBaliviere. We put a tower up right through the middle of the building. On May 13, 1960, the fire got us. And of course, it melted the steel tower legs inside the building and the tower fell into the parking lot.”

The pair started rebuilding immediately, getting back on the air with reduced power in five days. Only one local radio station manager offered to help: Bob Hyland from KMOX. And with the rebuilding came experimentation. Bench designed schematics for a stereo FM transmitter at about the same time General Electric and Zenith were building their prototypes.

All three stations went stereo the same day, WSYR in Syracuse with the GE system, WEFM in Chicago with Zenith’s system and KCFM here in St. Louis with Ed Bench’s creation.

The Bench/Eidelman team worked well together, even when it meant climbing the DeBaliviere tower to tweak an antenna or sawing a hole in the door of a sealed transmitter to prevent electrical arcing. “Harry was always coming up with ideas. If I couldn’t solve the problem, Harry would eventually have a solution. He’s a real brilliant man.”

After Eidelman sold KCFM, Bench stayed at DeBaliviere working for KSD-FM and then KMJM, retiring December 31, 1992.