Radio Articles

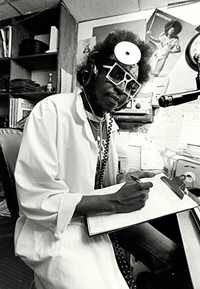

Dr. Jockenstein – Operating On Your Mind

by Kerry Manderbach

“This is Doctor Jockenstein…operating on your mind. Here on W-W-W-W-ESL, East St. Louis!” Who is Dr. Jockenstein? And how did he get his degree in DJ-ology? For the answers read on…

ockenstein was born Roderick G. King, and was brought up with his siblings in East St. Louis, IL. His mother had a stereo and would buy 45’s which Rod loved to listen to. Growing up, Rod attended Rock Junior High School where one of his teachers was Mrs. Brooks, mother of KATZ personality Donny Brooks.

Attending East St. Louis High School, Rod got his first taste of the radio business in the late Sixties while doing an internship at KATZ-AM in St. Louis. Listening to Donny Brooks on KATZ, Rod approached him and offered to be his “gopher,” telling him that “Your mom was my teacher.” He started lugging the equipment Brooks used at his personal appearances and soon was helping Brooks out at the radio station. As Rod described it, “…Actually I did an internship (back in those days they called it a ‘gopher’) at KATZ in 1968, then the word ‘gopher’ became internship. So I would hang around the radio station and go for coffee—anything they wanted me to do.”

After graduating from high school, he attended Southern Illinois University at Carbondale on a law enforcement scholarship through the East St. Louis community relations department. However, he had been bitten by the DJ bug and began spinning records for campus sororities and frat house parties. After 2 years at SIU-C, he decided his classes were “obsolete” and left school to plot his entry into the broadcasting business.

Back at home, Rod began throwing parties in his basement, calling them “Bluelight Basement Parties,” while spinning records in his new persona as “Touché The DJ—The Jock That Never Stops.” The parties were always popular, drawing large crowds. It was about this time that “Super Soul 1490” WESL-AM radio program director “Gentleman” Jim Gates noticed a drop-off in attendance of the parties he was throwing. “I remember I used to give parties and it was almost empty,” says Gates. “I found out Jock was giving a party at the same time and it would be packed out, I mean jammed. He knew everybody. He could entertain. So I figured if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. So I hired him.”

Joining established WESL DJs like Charles Edward Smith and Curtis Soul, King as ‘Touché’ started perfecting his on-air persona over the next year. “He had no formal training,” says Bernie Hayes, a legendary St. Louis radio figure and close friend who worked with King on occasion. “He learned the business from Jim Gates and Donny Brooks. I met him when Gates and Brooks came over to KWK, and Rod was lugging records around for them.” At WESL he tried to reach the audience with his unique style of banter, and playing the hits of the day by artists like The O’Jays, Earth Wind & Fire, The Dramatics, and The Stylistics.

While playing this traditional “soul” radio station fare along with early disco hits by Donna Summer, Tavares and KC and the Sunshine Band, King was also spinning more and more of an R&B style known as “funk”, which was slowly but surely replacing “soul music”. Younger listeners were gravitating to a grittier sound than their older brothers and sisters, preferring the likes of the Ohio Players, the Fatback Band, and Kool & The Gang.

Correspondingly, King put an emphasis on this style of music, and later remembered “Gates used to say ‘what IS that you’re playing?’” Many of the funk cuts King was spinning were produced by a group known as Parliament-Funkadelic.

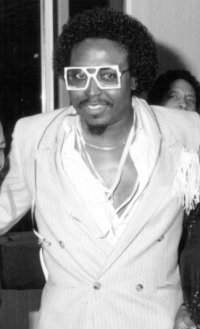

Riding herd over this conglomeration of musicians was future Rock and Roll Hall of Famer George Clinton. Clinton, also known as “Dr. Funkenstein”, brought Parliament to St. Louis on their “Mothership Connection” tour in 1976. Gene Robinson, a local performer known as the King of the Hollywood Blues, was acquainted with both Clinton and King and arranged a meeting between them. King ended up emceeing the St. Louis Parliament show, and the party afterwards. King later recalled, “I was working the gig and just like the album cover, I was dressed up like a doctor, trying to be the George Clinton Jr. All 20 of those guys came by and we just partied. At the end of the gig George said ‘Wait a minute, if I’m Dr. Funkenstein, you’ve got to be Dr. Jockenstein, the Mad Doctor of music behind the turntable.’” “He’s just like one of the band members,” Clinton said in a later interview. “He was totally into the group when we first started coming out that way, with ‘Chocolate City’ and ‘Up for the Down Stroke’. He was a big fan when he first started coming onto the radio. I remember him selling flashlights at the ‘Flashlight’ tour.”

With his new identity in place, Dr. Jockenstein started to pick up a wider fan base. He developed a new tagline: “This is Dr. Jockenstein…operating on your mind”. Soon, he took hold of an idea from the past…High School Roll Call. Bernie Hayes and DJ Jake Jordan had their own versions of shows called ‘Roll Call’. “I started ‘Roll Call’ at KATZ in 1966” says Hayes. “I would have the kids call in. Jake Jordan came in to KWK in 1969-1970; he also had a thing called ‘Roll Call’. When Jock became a disc jockey he then started what was called ‘Roll Call’ and it caught on pretty good.” “Jim Gates….put me on morning drive”. King said. “Going to work one day I was trying to think of something that would get the kids up to go to school…Then I got to saying, ‘Okay, it’s Roll Call time. Call in and say your name, your zodiac sign, and what school you attend.” Jock led his callers through the drill asking the questions in rhyme, and then let them loose with their own home-made raps. Thus, Dr. Jockenstein and his teenage callers were perhaps among the first ‘rappers’ on commercial radio.

The callers had to have something to rhyme to, so playing in the background of ‘Roll Call’ was what teenagers of the time called ‘skating music’. This was essentially an instrumental version of a contemporary hit, usually on the flip side of the record. These were radio station promotional copies, distributed by the record companies for DJs to play while doing a local ad. With no lyrics, the DJs could talk about the product they were selling and listeners may associate the product with one of their favorite songs. DJs also used these records in the part-time jobs they usually held, many times spinning records at the local skating rink. Jockenstein used the instrumental versions of hits like Chic’s “Good Times” for the ‘Roll Call’ show. ‘Good Times’ was also used as the backing track on the first commercial rap record, “Rapper’s Delight”. He also used other contemporary hits like Change’s “Lover’s Holiday”. “The ratings were great!” King recalled. “I had letters from Southwestern Bell to change the time I was doing the ‘Roll Call’ show, because I was tying up the switchboard, believe it or not.”

A typical ‘Roll Call’ segment would start off:

Here we go on the ra-di-o, I’m the DJ jock in ster-e-o. We’re gonna have a good time, On the Roll Call line’ (Freeman). On the go—on the radio! WESL!

Then Jockenstein would ask his callers:

Hey, what’s your name? What’s your sign? Give me that Number 1 school? Your favorite teacher with the Golden Rule? Your favorite station in the nation?

Or a variation:

Enie-meenie-minie-mo, let’s jam on the radio! Are you ready—like Freddy—to rock real steady? Said what’s your name? What’s your sign? Greatest school in the nation? Your favorite teacher with the education? Rock with it—what’s the greatest station in the nation?

By this time, King’s original 1 hour show had turned into an entire 4 hour program. He stayed at WESL until 1979, and then got an offer to be the program director of competing KATZ-AM / WZEN-FM. “They wanted Gates,” said King. “Gates asked at the time for some astronomical figure. And they said ‘Well, we’ll just take Jock’ and they brought me over and made me Program Director.” King became a Renaissance man during that period. “I think I wore every hat…Program Director, Music Director, Assistant General Manager, garbage man…(laughs)…Operations Manager, I did it all.” He also got a chance to work with Jim Gates again when the two of them did a morning program in 1992 on KATZ-FM, which had succeeded WZEN. “We had so many listeners I got scared” Gates recalled. A few years later, he was also heard on KNJZ (Z-100) with a blues-oriented program.

But FCC de-regulation was soon to cut a swath thru the radio industry, the St. Louis market included. “As I reflect on it now,” King lamented, “that was the end of community radio as far as the urban area or the Black neighborhoods were concerned, because…it was all corporate business.” After changing hands several times, the stations were bought by Clear Channel Communications and King was removed from his managerial duties and put on the air at KMJM-FM (Majic 104.9) part-time. “They kept him as a disc jockey, but not in an administrative capacity.” recalls Bernie Hayes “He got his training on the job for his administrative duties. And his disc jockey duties, as you know, where from the street.” Says King, “I went from full time different management positions to part time radio.” As voice-tracking became popular in radio King saw the changes and challenges ahead. “The way I look at it now, I grew up on personality radio, that’s how I was trained. And through the days of KATZ and WESL we still had that going where you felt [you were] a part of your audience because you were in the community.” “We’re in a situation now,” he continued, “where through the computer we can do our show a day ahead of time and be at home listening to it. To me it’s a scary situation. There’s no community effort being put out by the radio station, through the radio station, there’s no connection with your audience.”

Rod King had been spinning records for his “Jammin’ Oldies” show on Saturdays at Majic for about two years when, in early 2002, something went wrong. “Jock became ill, we were aware, when Deneen Busby and others at Majic said he was having all kinds of headaches,” Bernie Hayes recalls. “And a few times he got lost going to and from the job. And those are some serious indicators.” King was checked into DePaul Health Center in Bridgeton, MO where he lapsed into a coma. Thousands of fans contacted KMJM to inquire about his health, and several fundraisers were held to help out with medical expenses. In April of 2002, King’s old friend George Clinton gave a benefit concert at Pop’s nightclub, featuring blown up pictures of Jockenstein and a ‘Roll Call’ performance. The benefit was sponsored by WFUN-FM (Q-95.5), a competitor to Clear Channel’s 103.3 The Beat. “It’s not about the war [with The Beat] with this” says Q-95’s Craig Blac. “We know he’s an icon.” Other benefits were sponsored by Majic 104.9 at The Ambassador featuring local DJs along with Millie Jackson and Kenny Lattimore. “Jock is a legend in St. Louis, and he means a lot to me” says King’s Majic co-worker Deneen Busby. “He’s the one who put me on radio.” A benefit was also held at The Pageant featuring Ali, Doug E. Fresh, and Slick Rick.

Over the years, Rod King met Bobby Bland, BB King, Tyrone Davis, Al Green, Aretha Franklin, Smokey Robinson and The Temptations. He also toured for two months with Marvin Gaye, and went on tour with Parliament-Funkadelic, emceeing for them at Madison Square Garden. King received several awards, including 1997 DJ of the Year by Black Radio Exclusive Magazine, R&B Radio Personality of 1995, The Black Achievement Award from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, AM Personality of the Year two times, and one of the 100 Golden Voices twice by Gallery Magazine.