Radio Articles

Garnett Marks, WIL Announcer is Aviator and Writer

Garnett A. Marks, born March 21, 1899, at St. Louis, Missouri, educated in and graduated from St. Louis grammar and high schools, enlisted in the 138th U.S. Infantry shortly after graduating from Soldan High school in the class of January 1917. Served in this regiment until discharged because of prolonged illness at Camp Doniphan, Ft. Sill, Oklahoma. Returned home and after return to health joined the ambulance corps of the American Red Cross, serving as a driver of this unit in France until after the Armistice.

For several months after returning to the states was engaged in newspaper work as a reporter in Philadelphia, then became interested in aviation and served as an observer and photographer with the 13th Squadron, Surveillance, at Kelly Field, San Antonio, Texas.

First entered radio with KFI, Los Angeles, as a “song plugger” for a Los Angeles music publishing house. Later he became staff baritone and announcer.

In the autumn of 1926 he returned to St. Louis, and joined the KMOX staff.

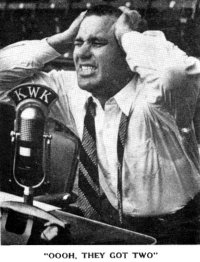

He was offered the position of sports announcer for KMOX, and throughout the seasons of 1927 and 1928 Garnett broadcast every game played in St. Louis, and on rainy days and open dates he could be heard giving play by play accounts furnished by ticker of the most important out of town game on such days.

Thousands of letters attested to his popularity and outstanding success as a baseball announcer and the opinion was almost unanimous that he was without peer in this line of endeavor. As a reward for his untiring and exceptional efforts to faithfully serve the vast audience with accurate, up to the minute and interesting baseball dope for 1928, Garnett was given a trip to New York to witness and help describe via the Columbia network the opening games of the series between the Yankees and the Cards played in the Yankee Stadium there.

In 1929, he returned to the Pacific Coast, singing in numerous sound productions created on Hollywood lots.

When work before the movie microphone was slack, he free lanced among several of the Hollywood and Los Angeles radio stations as announcer and singer. Late in 1930 he received an excellent offer from WENR, Chicago, to come on there as an announcer, and immediately installed himself as a favorite with the listeners of that station, which was absorbed by the NBC on March 1st, 1931.

So it was not long after that his friends throughout the land heard him as a network announcer on programs emanating from the Merchandise Mart, Chicago.

Because of the uncertain health of his father, Garnett returned to St. Louis late in November of 1931. He became an announcer at KMOX.

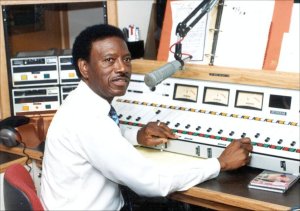

Recently he joined the staff of WIL, where he has taken over the Breakfast Club Express and can be heard every week day from 7 to 9:15 a.m. He also acts in the capacity of WIL news reporter. His hobbies are writing and aviation, the latter not altogether meeting with the approval of his family. His favorite sports, many of which he still indulges in, and the order of their popularity with him, are swimming, football, baseball, and horse back riding. He is married and has a charming young daughter.

(Originally published in Radio & Entertainment 7/16/1932).