Radio Articles

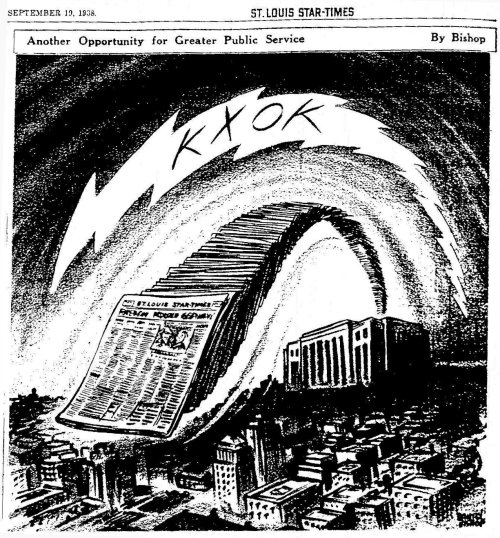

An Original KXOK’er

Bob Hille has fond memories of his work at KXOK and the day the station signed on.

“KXOK went on the air with a really impressive staff. We had a full studio orchestra. We had a classical quartet which included a man who played first cello with the Symphony. We had Skeets Yaney and the hillbillies in the morning. Eddie Arnold was a young kid who played with them. I went on as a studio announcer, which meant I was literally working for nothing. When I finally got a job that paid, which was in April of 1939, I made $40 a week, which was pretty good money in those days.

“The biggest name talent,” according to Hille, “was a young man named Paul Aurandt. He now goes by ‘Paul Harvey.’ Paul was kind of a second fiddle on special events. Allen Franklin did most of the really special events, as well as being program director.

“We had a very big studio set-up, including one studio with a full organ. The night before we went on the air, the union came up with the idea that we couldn’t do it because the organ had not been made by a union shop. Ray Hamilton, the manager, had to hire a guy to come in and sit down and put a hot soldering iron on every connection in the organ.”

The KXOK studios were on the fourth floor of the Star-Times building at 12th and Delmar, occupying the part of the building that faced 12th. The other side of the building housed the paper’s linotype operation, which caused a lot of noise and vibration. Hille says, “All three studios were mounted on springs, which was fairly innovative at the time. We had a disc recording set-up that was designed to escape the vibration from the linotypes. They mounted a Presto recorder on legs that ran down about three feet to a huge concrete block. The block was set on top of a large, inflated truck inner tube that kept the vibrations out.

“We did a lot of remotes. We were at dance halls practically every night. I remember we carried a live broadcast from the big circus that was playing at Kiel. Allen Franklin bribed the charioteers who were racing to stage a huge crash right in front of his broadcast position. Allen was really good.”

One might assume today that the Star-Times owners would realize the radio station would cannibalize some ad dollars from the paper, but in those days, more than money was at stake. “They were watching that combination down the street, the Post and KSD (at 12th and Olive). And there was a different group of advertisers, those who couldn’t afford ads in the newspaper.”

As a night announcer, Hille was required to do station breaks, news cut-ins and commercials. “If a half-hour program was on the air, you sat and, theoretically, studied your script, which is a laugh. Almost all our commercials were done live, since there were few recordings. Those would have to be done on disc, which was expensive. We did 15 minutes of news at 6 and again at 10, and a sign-off news at midnight.”

Later, after he was hired as a full-time announcer, Bob Hille was made host of a daily remote broadcast from various grocery stores where he would conduct a live quiz with shoppers. The program was sponsored by Forbes Coffee Company. After awhile he hosted a daily half-hour luncheon show at the Forest Park Hotel, which would feature celebrity guests.

There were seven or eight radio stations serving the St. Louis audience in the late 1930s, and Hille says the big difference in the stations was determined by whether the station had a network affiliation. “NBC was split into the Red and Blue networks at that time. We had the Blue. KSD had the Red, which was the premier. KMOX had CBS. KWK, with Mutual, was not as big. So that made KSD an even bigger competitor for KXOK, and in this case, the competition was accelerated because of the personal competition between the newspapers’ publishers.

That competition even spread to talent raids. In 1951, Bob Hille was hired away from KXOK to work as an announcer at KSD and KSD-TV.

(Reprinted with permission of the St.Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 09/03.)