Radio Articles

A Flack’s View of KXLW

Early fans of radio marveled at its ability to create a theater of the mind in which listeners were able to “see” the things they were hearing on the radio. The performers and sound effects people prided themselves in their ability to create this vision of unreality. As the medium matured, at least one St. Louis station used the same concept in a promotional brochure.

When KXLW signed on January 2, 1947, general manager Guy Runnion had visions of his little 1,000 watt daytime station becoming a major player in the market. He’d been a newsman on KMOX in the early ‘40s, and now he and his wife Gladys had controlling interest in their own station.

Their 28-page brochure, “Going Forward With Radio, as presented by KXLW,” promoted the image of KXLW as “your Neighborly Golden Circle Station.” It was distributed 10 months after the station’s sign-on. The brochure, representing the best work of public relations director Edgar Mothershead, showed a station filled with men and women in an exciting environment. But if you read between the lines, you see some cracks in the façade.

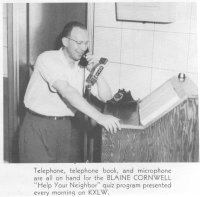

There’s the story of Director of Programs Blaine Cornwell. He’s shown interviewing visiting musical artists, hosting two daily disc jockey shows and hosting a morning quiz program, lots of responsibility for one man. General manager Runnion appears in photos interviewing a guest on the air, which wasn’t a common function for many station managers in those days. One of the station’s sales people, Pat Kendall, is identified as “one of the few women possessing a degree in architectural engineering,” a somewhat dubious honor for a radio time salesperson.

Spider Burks, St. Louis’ legendary jazz disc jockey, has his name spelled two different ways under two different photos, and does Reid Brooks, the station’s news announcer. One photo of Blaine Cornwell posing with a music group is printed backwards, resulting in the station call letters on the mike flag showing up backwards.

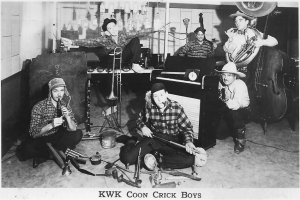

There’s a picture of a man dressed in the full regalia of an Indian chief, standing in front of a microphone with a tom-tom. The cut line reads, “Little Beaver, editor of the ‘Outdoor Magazine of the Air’, presents news and comments of interest to the sportsmen.” One can only imagine how this program must have sounded on the air.

The brochure contains two photos showing the crowded, bustling news rooms of the Associated Press in New York City, which, of course, did nothing more than provide the station with wire copy.

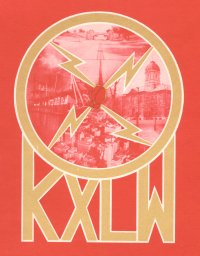

The biggest mystery is the “Golden Circle” referenced throughout the booklet. KXLW is called the “Golden Circle Station” and there are other notes giving the impression that a specific geographical area is the “Golden Circle,” but there is never a definition provided. The brochure’s crimson back cover has a gold circle in the middle around the words, “KXLW Serves the Golden Circle.”

In short, it must have seemed like an excellent promotional idea, but the reality portrayed in “Going Forward with Radio” probably didn’t venture far from the truth. KXLW, at its inception, was doomed to be nothing more than a second-tier St. Louis radio station.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 10/05).

Ed would often hold me through a commercial so I was trapped when he went back on the air. And, he frequently used these opportunities to give me a hard time – ‘Well, well, little Bobbie, the son of the boss. Isn’t that uniform cute?’ and ‘Do you have a girlfriend?’

Ed would often hold me through a commercial so I was trapped when he went back on the air. And, he frequently used these opportunities to give me a hard time – ‘Well, well, little Bobbie, the son of the boss. Isn’t that uniform cute?’ and ‘Do you have a girlfriend?’