Radio Articles

KSHE Station History

KSHE was granted a construction permit on September 7, 1960 for a new broadcast station at 94.7 mHz. A license to broadcast was issued June 15, 1961. The license was owned by Rudolph Edward Ceries, who went by the name of Ed. He and his wife broadcast from the basement of their home at 1035 Westglen Drive in Crestwood.

Mr. Ceries had previously worked as an engineer for twenty years at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch broadcast properties in St. Louis, KSD and KSD-TV. He literally built some of the original KSHE equipment himself. He and his wife also helped with announcing duties.

KSHE was dubbed “the lady of FM,” and the station’s format began as all classical, later shifting to emphasize the arts, playing classical, semi-classical and light music. Radio drama was also broadcast, with the typical day running from 7:45 a.m. to 12:30 a.m. They employed one full-time and two part-time announcers.

In 1962, ownership was transferred to Crestwood Broadcasting Corporation (Robert H. Orchard, E.V. Lowall, Keith S. Campbell and Rudolph E. Ceries. They sold the station to Century Broadcasting, effective October 1, 1964.

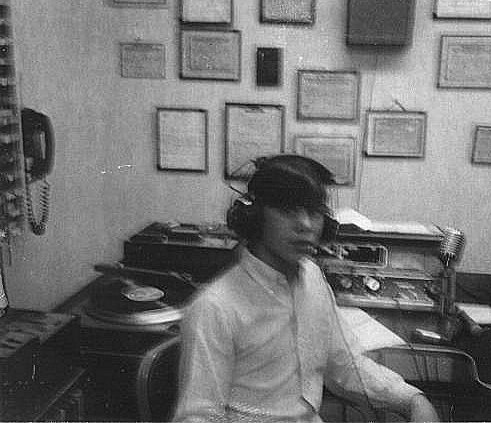

The new owners changed the station’s format to “progressive rock” in 1967 in an effort to turn a profit. Although there is a St. Louis disc jockey who claims credit for the change to rock music, no documentation has ever been found to back up his claims. By the end of the ‘60s, KSHE was becoming one of the nation’s leading “underground” radio stations. The studios and tower were located at 9434 Watson Rd. (Highway 66) in Crestwood. This site became renowned as a pseudo-shrine among listeners and employees, as listeners had easy access to announcers in the small, cinderblock building, which had a drive-up window from a previous incarnation.

Manager Sheldon “Shelley” Grafman is fondly remembered by his staff as a guy who made the whole thing work. He served as GM, sometime PD, sales cheerleader and collection agency. Realizing the need for a bigger identity, the station applied for and received permission to identify itself as “KSHE, Crestwood-St. Louis” in August of 1973.

In 1984, owner Century Broadcasting sold KSHE to Emmis.