Radio Articles

KFRH 400 kHz, et. al.

The station, at 570 kHz, was a carrier-current student operation at Washington University.

The station, at 570 kHz, was a carrier-current student operation at Washington University.

Anyone who remembers the Dogpatch characters created by the late cartoonist Al Capp will probably remember Joe Btfsplk. He was the poor soul who walked around with a black cloud hanging over his head. For him there was never much chance of basking in the sunshine of good fortune. So, it seems, was the fate of radio station KFQA in St. Louis.

Owned and operated by The Principia, KFQA hit the airwaves May 9, 1924. In those days The Principia was not at Elsah, Illinois as it is now. It was located in St. Louis’ West End at 5539 Page. A bill of sale from Western Electric Company shows the entire equipment package cost less than $5,000, installed. In fact, the school paid to bring in a special radio engineer from Chicago to handle the installation, and he charged them $1.90 to cover expenses for two meals. All these costs were paid by a benefactor, Clarence Howard, chairman of the board of General Steel Castings in Granite City. Two 62’ masts were constructed atop Howard Gymnasium 85’ apart and the aerial was strung between them. The studio was built in a 12’X12’ room, and the first transmitter had a power of 50 watts. There were unconfirmed reports of reception of KFQA along the Eastern seaboard.

It is clear from all documents in the Principia archives that the primary raison d’être for the station was to broadcast local Christian Science church services and lectures.

In radio’s early days two or three stations were often required to share the same frequency, and when KMOX signed on in December of 1925, it was given the same frequency as KFQA. Along with KFQA’s new neighbor came a new, powerful transmitter, 5,000 watts. The Principia station would be allowed to broadcast, without charge, over the frequency 104 hours a year. This arrangement had a two-year life span, and then KFQA had to start paying for broadcast time, which totaled about 64 hours a year. The cost, including remote line charges, would be $5,327.00.

Soon the Federal Radio Commission began to question whether The Principia should be allowed to continue operating a radio station. KFQA had been forced to change frequencies in 1927, from 1150 Kc. to 1210 Kc. (shared with WMAY), and later to 1280 Kc. (shared with KWK and WMAY). In May of 1928 the station was ordered to leave the air, but they were back on in October of that year, again sharing a frequency with KMOX.

It was an interesting arrangement. KMOX was obligated to broadcast the Christian Science church services. KFQA was obligated to buy shares of the corporation owning KMOX and pay the station the equivalent ad rates for the broadcast time. And KMOX would be identified as KFQA during those broadcasts.

This arrangement, convoluted as it was, stayed in place until July of 1930, when the Federal Radio Commission deleted the call letters of KFQA from its active files.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 04/01)

Photos courtesy of the Principia Archive, Elsah, IL. All Rights Reserved.

KFQA was a short-lived radio station that spent most of its life sharing

frequencies with other St. Louis stations. That seemed fine with the owners, however. They didn’t really need a lot of time on the air.

When the station was licensed in May of 1924, The Principia was listed as the owner. All The Principia seemed to want was a frequency on which they could broadcast their Christian Science church services. Since it was not uncommon in 1924 for a radio station to only broadcast a few hours a week, this goal was understandable.

As more and more radio stations applied for broadcast licenses, it became clear to Washington officials that an oversight organization was needed to administer broadcasting, and the Federal Radio Commission was established in 1927. It was this group that paired up radio applicants and assigned frequencies on the AM band. The results were often fraught with disagreement, much like siblings fighting over the slightest provocations. (one such battle, involving the shared frequency assignments of KFUO and KSD, lasted almost 16 years.)

Printed records show KFQA bounced around several frequencies, variously landing at 1150, 930, 1280 and 1000 kHz.

When it became evident to Washington policymakers that they had too many radio stations for the number of active frequencies that were available, KFQA was assigned to 1280 kHz, along with Benson Broadcasting’s KWK and WMAY, which was another church-related station owned by the Kingshighway Presbyterian Church. This lasted only a few months.

On May 28, 1928, KFQA was told by the Federal Radio Commission that it would lose its license under a radio reorganization plan. Appeals were filed, but the station was finally forced to shut down in September. The battle had not ended, though.

After more wrangling in Washington, The Principia emerged victorious. They were given permission, under a unique arrangement, to broadcast on another station’s frequency, using that station’s equipment and transmitter, while identifying themselves as a separate broadcast entity, KFQA. The new partner was KMOX.

Under the FRC orders, KFQA aired services from the Fourth Church of Christ, Scientist, every Sunday at 11:00 a.m. over KMOX, which was, only during that broadcast, identified as KFQA. The newspaper article announcing the arrangement indicated it was to begin October 7, 1928, little more than a month after KFQA had shut down. There were to be other lecture programs set up at a later time. This frequency sharing arrangement was to last for one year. The article was the last mention found of KFQA.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 3/00)

The grand experiment that was KDNA in the 1960s appears to be part entrepreneurial, part pie-in-the-sky and part fun. It didn’t work, mainly because voluntary donations from listeners couldn’t overcome the station’s red ink.

Ostensibly the brain child of Jeremy Lansman and Lorenzo Milam, KDNA-FM went on the air on February 8, 1969 on a commercial FM frequency, 102.5 mHz. The two men had met in Seattle at a similar type of radio station with the call letters KRAB. Lansman had dropped out of Clayton High School here and gone to radio school.

Milam reportedly put up $50,000 to start KDNA, but it was several years before the Federal Communications Commission granted the duo a license because there was a competing application for the frequency from the First Christian Fundamentalist Church. There were even charges that the radical group Students for a Democratic Society was behind the station’s founding, a charge Lansman denied.

KDNA developed a loyal audience among students at both Washington and St. Louis Universities. Staffers were paid, albeit not much, to do their programs, and Lansman told listeners he wouldn’t sell ads so long as their voluntary contributions covered costs. Studios were at 4285 Olive in Gaslight Square in an old house. Lansman, his wife Cami and their young son lived upstairs, and rooms on the house’s third floor served as a dormitory for some staff members.

Some might call the programs wonderfully “free-form.” Music seemed to have no sense of format except that the songs heard were those the disc jockey wanted to play. Listeners were treated to unexpected monologues espousing personal opinion or discussions of social problems. There were on-air conversations with Jeannie, the affectionate name for the station’s transmitter, sometimes chastising her for allowing the frequency to wander. The St. Louis Symphony’s Leonard Slatkin would drop in every Thursday afternoon to spin records.

But there were detractors.

These were the late 60s and early 70s, and anti-war tensions ran high. People with long hair were deemed the enemy by many.

Police raided the KDNA studios on a drug search. Lansman and two staff members were charged with violating the state’s drug laws. Lansman said the drugs had been planted. The charges were later dropped. A very vocal challenger appeared in the person of evangelist Bill Beeny, who sought to have KDNA’s license assigned to himself and lawyer Jerome Duff.

They ultimately failed, and so did KDNA. The writing was on the wall for the station’s demise when it began a “pledge drive” with a goal of $400,000 and collected only $20,000. Lansman had said he would use the donated money to cover the station’s debt and buy out Milam’s half. The remainder, he said, would be used to form an umbrella group to oversee community radio in St. Louis. The group’s name, he said, would be Double Helix Corporation.

Lansman sold the station to Cecil Heftel for $1.4 million in 1972 and the call letters were changed to KEZK. Proceeds of the sale were split 50/50 between Lansman and his partner Milam.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 10/97)

It was the early days of FM radio. March 27, 1955, owner Harry Eidelman signed on his new FM station in St. Louis, KCFM. Studios and tower were in the Boatmen’s Bank Building on Olive downtown. Later, Eidelman moved to a new location to save money.

With the help of broadcast engineer Ed Bench, Eidelman moved the entire operation, including the broadcast tower, to an old warehouse at 532 DeBaliviere. The new 300-foot steel tower was self-supporting and didn’t need guy wires, but the legs literally came down through the building’s roof and were anchored in the floor.

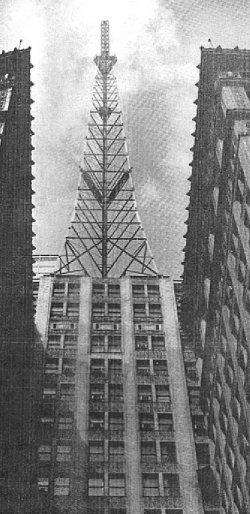

Original KCFM tower atop the Boatmen’s

Bank Building on Olive downtown.

At the time of the move, KCFM was one of six FM stations serving the market. Theirs was a “beautiful music” format, but advertisers were reluctant to put their money into the relatively new medium and the station operated on a shoestring budget. Two of the FM stations here were non-commercial.

Things went smoothly, until the night of May 12, 1960. That’s when Eidelman got a phone call at home around midnight from Walter Vernon, the announcer on duty, who said he saw smoke in the studio coming out of an air conditioner. Writing about the incident later in the Post-Dispatch, Eidelman recalled he “gave him the only advice I could come up with at the moment! Call the fire department and get the heck out of there.”

Vernon, the announcer, did as he was told, and the janitor on duty was quick to follow. The first alarm was struck at 12:12 a.m. At about the same time, someone passing by the building saw smoke and ran to Engine Company 30 at 541 DeBaliviere, across the street from the studios, to alert firemen there. The radio station quickly filled with thick, black smoke and flames burst through the roof, causing another major problem.

The excessive heat had begun to melt the steel tower legs.

Within moments, the huge tower came crashing down. It fell to the north, into the National Food Store at 546 DeBaliviere, setting off that building’s sprinkler system. Multiple fire alarms were called with a total of 25 pieces of fire equipment and 100 firemen dispatched to the scene. It took firemen several hours to get the situation under control, and Harry Eidelman’s radio station was set at over $50,000 – a total loss.

The supermarket suffered smoke and water damage and there was also smoke damage in the nearby Winter Garden Skating Rink, The Toddle House and Hampton Cleaners. Two firemen suffered minor injuries on the scene.

In his Post-Dispatch article, Eidelman wrote, “…there was nothing left of the building that had been KCFM. DeBaliviere looked like the Fourth of July. Within an hour, every member of the staff was standing in the street looking at the ruins.

“The next morning we gathered at the ashes and tried to decide where we could go with KCFM now. We could take the insurance money, which would not pay off one-third of our bills, and fold up. Or, we could try to rebuild something. The consensus of the entire staff was, let’s go forward. They even offered to go without their paychecks until we were back in business, but that didn’t become necessary.”

Ed Bench remembered, “I salvaged a transmitter cabinet and all the parts I thought I could use. We rented a storefront across the street and I cleaned up the stuff I had salvaged and built a one kilowatt transmitter.”

Within five days KCFM was back on the air, operating with reduced power and using space on its old tower atop Boatmen’s Bank, which was, by then, the primary tower for KETC-TV (Channel 9). Within a few more days, KCFM was operating at full power. Ed Bench recalled in a later interview that only one of the market’s radio managers offered help: Robert Hyland of KMOX.

Eidelman reminisced about those trying transitional days several years later. He told a Globe-Democrat reporter he was listening one night a few weeks after the fire when the music suddenly stopped. He rushed downtown, took the elevator to the 19th floor, ran up the last two flights of stairs and rushed into the studio, where he found his announcer fast asleep, the classical record still spinning with the turntable needle at the record’s center.

A year later, KCFM’s DeBaliviere location had been completely rebuilt, along with a 500-foot tower at the site. In 1978, Harry Eidelman sold KCFM to a national corporation, Combined Communications.

(Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Journalism Review. Originally published 5/08.)

The call letters KBMJ were originally assigned to the radio station at the University of Missouri – St. Louis.

Official assignment came on December 27, 1968, however the station did not go on the air until 1972. By that time the call letters had been changed. The FCC granted the calls KWMU on April 11, 1969.